The Caribbean Gang Problem

LinkedIn: Addressing Gang Violence in the Antigua and Barbuda: A Blueprint for the Caribbean

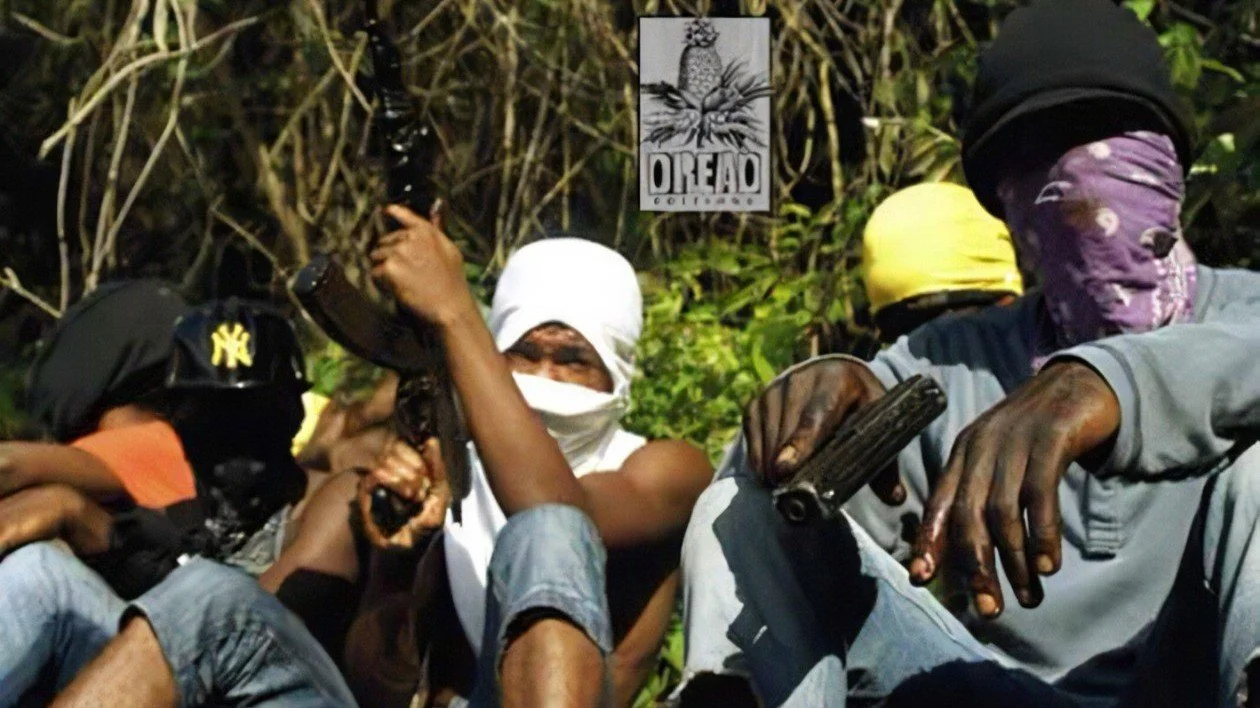

When most people think of the Caribbean, they often picture luxurious beaches and scenic mountains, perfect for a family vacation. However, underneath what appears to be islands full of rich ecosystems and culture, lies a deeper problem in the rapid spread of gangs across the region. Violence has skyrocketed as of 2025, with Haiti having a 78.9 crime index, followed by Trinidad at 70.9 and Jamaica at 67.4 (measured on a scale of 0-100). Gangs fight to control huge swaths of territory, and innocent civilians are caught in the crossfire as governments fail to protect them properly. Gangs are an issue of governance, and in order to protect their citizens, North American nations must form a united plan to implement effective governmental policies.

Since the assassination of President Jovenel Moise in 2021, Haiti and its government have collapsed. An attempt to establish a nine-member council to provide stability until the next election failed on account of multiple charges of corruption. Without any clear power structure present, gangs were able to roam freely, competing with each other to secure as much influence as possible. By 2023, gangs had taken huge swaths of the capital of Port Au Prince. Since then, these gangs have induced mass killings that have significantly affected the community, claiming around 1,000 lives since October 2024 and a record displacement of 1.3 million Haitians. Those who remain in Haiti are subject to brutal cruelty such as rape, stabbing, and kidnappings, to name a few. Now the violence has begun to spread outside of the capital, destroying vital infrastructures such as hospitals, apartments, and schools. Haiti’s gang problem shows no signs of ending, and it is rapidly becoming one of the biggest humanitarian crises faced.

While Haiti has been the most notable example of the rise in gang violence, other Caribbean islands have been subjected to similar fates. In Trinidad, gang-related violence comprised 40% of total murders within the region in 2024, leading to heavy criticism of the government, which has failed to act effectively. States of emergencies were also implemented in Trinidad as well as Jamaica within the last year due to persistent gang violence, in which police were granted the right to search and seize assets to aid in the peace-keeping process. Jamaica, specifically, has one of the highest levels of gang fragmentation, creating more volatile factions that rival those seen in Haiti. Police often engage in brutal conflicts with gangs, creating immense pressure. Puerto Rico has also been notorious for their gang presence, with clashes between gangs rising substantially to exceed last year's levels due to the rivalry between Los Viraos and El Burro. These gangs have even been labeled as transnational criminal groups by the Jamaican prime minister, Andrew Holness, who publicly stated that Trinidad gangs may have links to Jamaican ones. This ongoing transnational gang violence threatens the lives of innocent citizens, as one in ten children experience sexual abuse in Trinidad, and women continue to be subjected to domestic violence. With so many nations already being affected by the brutality of gangs, it is important to mitigate the issues as soon as possible, or fear other nations such as Grenada or Barbados becoming absorbed with gang violence.

When examining these Caribbean islands and their high rate of gang violence, there are a few common trends. Many of these nations, such as Trinidad and Haiti, have governments that suffer from a weak executive branch due to significant corruption and inefficiency. A weak central government results in weak institutions that fail to enforce the law, allowing gangs to roam around freely with very little resistance. When conflict arises, gangs are often more coordinated than official government responses because of a greater sense of unity. These Caribbean islands also heavily suffer from poverty and inequality, compounded by the ineffectiveness of the government in remedying these issues. Gangs take advantage of the socioeconomic gap, providing relief to those subjected to poverty in the form of food, water, clothes, and money. The result is people residing in those towns pledging loyalty to respective gangs because they have improved their lives, legitimizing themselves over the government. Finally, all these Caribbean nations are geographically trapped between the U.S. and Latin American illegal drug trafficking routes. Gangs smuggle drugs illegally into these Caribbean islands, selling to the U.S. in exchange for firearms. In nations such as Trinidad and Haiti, the illegal U.S. firearm market has yielded significant money for these gangs to help claim territory, leading to high murder rates that directly correlate with gun trafficking.

To help mitigate the violence of gangs, the Caribbean Community (Caricom) should coordinate a united policy with the U.S. This idea has already been presented at the Caricom Summit in July, with the St Kitts and Nevis prime minister, Terrance Drew, stressing the necessity of “the coordination of all of the member states.” The first act of Caricom should be to work with the US to negotiate for better security over gun trafficking, with the U.S. imposing much stricter policies and control when it comes to illegal drug and firearm trade, considering most of it goes to Caribbean gangs. Secondly, Caricom should look to break up the international connectivity of these gangs. This could be done through establishing a border task force, negotiating agreements on persecuting criminals if they flee to another island, and increasing funding for information centers. Thirdly, Caricom and the U.S. should provide some funding to Caribbean nations such as Trinidad and Haiti, which have severe issues of poverty. Providing some relief for these vulnerable communities decreases the likelihood that citizens will rely on gangs for survival.

Gang violence can be solved, as seen recently, where Jamaica, despite having high crime rates, decreased its murder rate by 40% for the first 5 months of 2025 by integrating new technology into law enforcement operations. Therefore, to ensure stability in the Caribbean, the issue of gang violence must be solved sooner rather than later.

Narco-Feminism Is a Lie: The Myth of Empowered Women in Cartels

Introduction: The Illusion of Power

In cartel culture, women hold guns, manage drug operations, and appear to wield influence. Social media, pop culture, and even certain feminist narratives frame them as powerful figures breaking into a male-dominated underworld. The rise of the buchona aesthetic—a hyper-glamorous, luxury-driven style associated with cartel wives and girlfriends—further fuels this perception. But does their presence in organized crime signify genuine empowerment, or is it simply another manifestation of patriarchy?

Choice feminism suggests that any decision a woman makes is inherently empowering. This logic extends to women who enter cartel life, assuming that if they choose to launder money, traffic drugs, or command sicarios (assassins), they are asserting autonomy. In reality, cartel culture does not liberate women—it subjugates them to a hyper-violent system designed to use and discard them. Radical feminism makes this clear: participation in oppression does not equate to freedom, as choices made within oppressive structures are often shaped by those structures. Cartel women may appear powerful, but their influence is conditional, and their survival often hinges on their relationships with men in power.

Women in the Cartel World: Authority or Survival?

While a handful of women have reached leadership roles in cartels, their ascent is almost always tied to male figures. For example, Enedina Arellano Félix of the Tijuana Cartel took control only after her brothers were arrested or killed, managing finances rather than commanding troops. Similarly, Rosalinda González Valencia, associated with the CJNG (Jalisco New Generation Cartel), handled financial operations but was ultimately arrested while her husband, a major cartel leader, remained at large. Sandra Ávila Beltrán, the so-called "Queen of the Pacific," leveraged her family’s cartel ties but ended up imprisoned, like so many others before her. These women may have wielded influence, but they were never at the top of the power structure. They occupied a position of authority because the men around them were temporarily absent and unable to do so.

Beyond leadership, women serve other roles in cartel operations, yet none offer true security. The buchona aesthetic is often presented as a symbol of cartel women’s financial independence because, on the surface, it visually signals access to wealth, luxury, and power. Women who embody this look typically display markers of high status—designer clothing, luxury handbags, dramatic makeup, and surgically enhanced bodies—which are conventionally associated with success and autonomy in capitalist, image-driven societies. It is, however, actually a reflection of control. Cartel-affiliated men dictate the physical appearance of their wives and girlfriends, funding plastic surgeries and designer wardrobes to fit a beauty standard designed to flaunt their wealth, even if it kills them. These women, though seemingly elevated by their proximity to power, remain vulnerable. If they lose their usefulness—whether through age, disloyalty, or legal troubles—they are easily replaced.

Others are thrust into direct criminal activity. Women are frequently recruited as drug mules because they attract less suspicion at border crossings. Some, like La Catrina, a high-profile cartel assassin, become sicarias themselves. However, many are coerced into these roles and given no real alternative. La Catrina, who became notorious for her involvement in cartel violence as a member of the Jalisco New Generation cartel, was dead by twenty-one, killed in a police raid. Her notoriety did not protect her, nor did it grant her the longevity or security enjoyed by her male counterparts. The promise of power in the cartel world is often a short-lived illusion.

Why Choice Feminism Fails

Choice feminism insists that women exercising agency—even within oppressive systems—are inherently empowered. This framework, however, collapses when applied to cartel women. While they may choose to enter the drug trade, that choice is rarely made in a vacuum. Many come from environments where cartel involvement is one of the few economic options available. Others are drawn in through coercion, manipulation, or familial ties. The argument that their participation is an act of empowerment ignores the structural conditions that drive them into organized crime in the first place.

Even for those who voluntarily enter cartel life, power remains tenuous. A woman’s influence within a cartel is almost always tied to a man—her father, brother, husband, or lover. Unlike their male counterparts, whose authority is recognized through force or reputation, women in cartels gain status relationally. The moment their connection to a male figure weakens, their protection disappears. They are not dismantling patriarchal structures, but operating within them, often at great personal risk. The notion that women gain equality by playing the same violent game as men disregards the reality that cartel structures were never designed for female autonomy.

Social Media and the Glorification of Cartel Culture

The romanticization of cartel life extends beyond the criminal world into mainstream culture, particularly through social media. Platforms like TikTok and Instagram promote an idealized version of the buchona lifestyle, showcasing extravagant wealth, designer clothing, and luxury cars under hashtags like #NarcoQueen and #CartelWife. These curated images create a false narrative that cartel-affiliated women live glamorous, consequence-free lives. Missing from these portrayals are the violence, domestic abuse, and lack of agency that many of these women face.

This glorification extends to music as well. Narcocorridos, or drug ballads, often depict women in cartel culture as either deadly and seductive or beautiful and submissive, reinforcing the idea that their worth is tied to their desirability or usefulness to men. Young women consuming this media may not recognize the disparity between the image and the reality. Instead, they see a path to financial security and status without realizing the inherent dangers of cartel life. The aesthetics of power should not be mistaken for actual power, and yet, social media blurs this distinction.

Conclusion: Narco-Feminism is a Façade

Women in cartels are not revolutionaries; they are participants in a system that was never built to protect them. The idea that their involvement represents a form of feminism ignores the realities of how power functions within organized crime. Holding a gun or managing cartel finances does not free women from patriarchy. Running a criminal operation does not shield them from the violence, exploitation, and disposability that define cartel life.

Choice feminism argues that because these women have chosen their roles, they are empowered. Radical feminism exposes this fallacy. True empowerment does not come from maneuvering within an oppressive system—it comes from dismantling it. If narco-feminism were real, women would not have to navigate cartel culture by the rules men established; they would be rewriting them entirely. But they aren’t. They are surviving, and survival is not the same as liberation. There is no feminism in a system built to destroy women. The only way forward is to reject the structures that keep them bound.

Incumbent Ecuadorian president reelected for another term

In a rematch between Ecuador’s two 2023 presidential candidates, Ecuadorian president Daniel Noboa won the country’s runoff elections held on April 13th, defeating Luisa González with a 10-point lead. The elections came after neither candidate won a majority in a snap election held on February 9th. While the conservative, banana-billionaire incumbent was quick to announce that he had secured another four-year term, his opponent, left-leaning lawyer González, demanded a recount of the votes that she claimed were the result of “grotesque electoral fraud.”

Previously, Noboa, at age thirty-five, became Ecuador’s youngest elected head of state in November 2023 after winning another snap election held following President Guillermo Lasso’s decision to dissolve the National Assembly to avoid an impeachment vote. After only serving a year and a half, elections were set to be held again on February 9th for the next presidency, which resulted in a “technical tie.” Noboa won 44.17% of the votes and González 44% (the third candidate Leonidas Iza had 5.25%). Voter turnout for round 1 of the elections was 82%, increasing to 84% in round 2 of the elections following a heated presidential debate.

While President Noboa expressed skepticism following the first round of votes, he has failed to provide any definitive evidence of election fraud or malfeasance, instead asserting that the “irregularities” were being reviewed in areas where the counts “did not add up.” However, in observations independent from the elections, both the Organization of American States (OAS) and the EU Election Observation Mission denied Noboa’s allegations of fraud.

Historically, an incumbent being successfully reelected in Ecuador is rare, yet, ultimately, issues with rampant crime and gang violence tipped the voters over the edge. With rampant crime stemming from cocaine production and narco-trafficking from neighboring countries Colombia and Peru, Ecuadorian citizens have fallen victim to violence across the country. While Noboa put this topic at the forefront of his campaign, González stressed different goals of increasing social spending to boost the economy and cut fuel prices—a message that ultimately didn’t resonate enough with voters.

Despite making modest progress in reducing crime rates and drug gang presence, Noboa’s past actions in implementing emergency military measures to curb crime and successfully reducing homicide rates, from 46.18 per 100,000 people to 38.76, swayed citizens into giving him another chance to produce more tangible results. González, on the other hand, garnered little attention in her various government positions over the years, until being selected by the RC (Citizens Revolution) as its presidential candidate in the snap election in 2023.

As a whole, the candidates shared some similar goals and policies, including endorsing continued oil drilling in the Amazon and weakening Indigenous governance rights. Third-party candidate and self-identified Marxist-Leninist Leonidas Iza, however, directly opposed these policies in his campaign, advocating for Ecuador’s Indigenous communities and powerful grassroots communities, the End Amazon Crude Movement, and the introduction of a new era of climate justice. While the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador (CONAIE) strongly aligned with Iza, with around 5% of overall national votes, much of the community was divided over which candidate would best advocate for their interests. The organization’s failure to fully assemble around one candidate called into question the organization’s ability to unify its members.

In recent years, President Noboa has aligned himself with other conservative presidents, including Argentina’s President Javier Milei, El Salvador’s President Nayib Bukele, and the U.S.’s President Donald Trump, even going further to align with Trump’s anti-immigration policies and declare a willingness to accept deportees. Ecuadorian citizens have shown disappointment in this alignment, believing that a relationship with President Trump should have already excluded the country from the 10% tariffs outlined for Trump’s “Liberation Day.” González even mocked Noboa when these tariffs were implemented following his informal visit to Mar-a-lago. Now, Ecuadorian citizens hope the new president takes the same strong stance against drug and crime rates, following through on his vows to fix the detrimental effects it has had on the country.

No, Maduro Won’t Invade Puerto Rico

CNN en Español

At a closing speech made at the Global International Antifascist Festival, Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro made claims about liberating Puerto Rico with Brazilian troops. He invoked Simón Bolívar’s goal of liberation from Western oppression to argue for the necessity of Venezuelan intervention. This threat was met with backlash from the Puerto Rico governor, Jenniffer González-Colón, who called it an “open threat to the United States.”

Maduro’s words, while aggressive, are all bark and no bite.

Following Maduro’s internationally rebuked re-election in July, this divisive move could be interpreted as an attempt to restore legitimacy in the wake of electoral discontent. This strategy, known as diversionary foreign policy, has been used by leaders to restore unity and patriotism around the state. Under this theory, the possibility of war could create a rally ‘round the flag effect that would invoke nationalist sentiment and restore internal cohesion, skyrocketing Maduro’s approval rating.

While the conditions may be ripe, and a conflict could generate positive effects for Maduro, waging a war with the U.S. would be a disastrous blunder. The U.S. is a nuclear-armed superpower whose military strength is unrivaled by any great power, let alone a smaller state like Venezuela. As such, any potential domestic political benefits would be largely outweighed by a decisive military loss at best, or at worst, a prolonged conflict with tens of thousands of military casualties. Furthermore, while Maduro’s re-election received the support of Russia, China, and Iran, it’s unlikely that any of them would support the state in a conflict, given Russia’s war with Ukraine, China’s domestic economic troubles, and Iran’s regional focus.

Ignoring the risk of a U.S. counterstrike, an amphibious invasion would be difficult to mount. Puerto Rico’s terrain is incredibly mountainous, with 60% of the country covered in mountains. Beyond that, it is unlikely that Maduro would be able to utilize Brazilian troops, as Brazil has no incentive to get involved in a war with the U.S. Given the increasing diplomatic estrangement between Brazil and Venezuela, Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva is unlikely to support such a move. While relations between the two states have historically been strong, Lula has pivoted recently, distancing himself from Maduro and openly critiquing the authoritarian regime and election outcome.

If Maduro were to wage a war, he wouldn’t go too far. Long-standing border disputes with Guyana over ownership of the Essequibo region have escalated in recent years, as Maduro has made similar references about liberating the oil-rich territory. In December 2023, Maduro unveiled a map of the country that included the Essequibo region, and has long announced his intention to take over the oil-rich region. While Maduro has made declarations domestically, Guyana has sought international recognition from bodies like the International Court of Justice to resolve these disputes. Given Venezuela’s oil-based economy, their comparative military dominance over Guyana, and Maduro’s reference to polls (albeit questionable ones) that show an overwhelming majority of Venezuelans would support incorporating the region into Venezuela, the Essequibo region seems primed for a Venezuelan invasion.

But once again, Brazil serves as the foil to Maduro’s plans. Lula has distanced himself from Maduro, improved relations with Guyana, and positioned himself as a mediator between the two states in their quarrel. While Maduro may scoff at the Guyanese army, he can’t ignore the Brazilian Army, who moved armored vehicles to their northern border to further deter Maduro from invasion. Lula’s military move comes after Maduro agreed to pursue diplomatic measures to acquire the region, indicating the growing mistrust between the leaders.

As such, the fate of Venezuela’s military decisions could end up being a question of Brazil’s positioning–specifically the degree to which Lula will seek to influence or restrain Maduro in his ambitions. Therefore, how Brazil navigates this thorny issue will play a decisive role in the region’s stability for the foreseeable future.

El Salvador: President Bukele’s landslide reelection raises concern for one party-state

Written by: Diego Carney; Edited by: Luke Wagner

Nayib Bukele, who is known for his strict anti-gang and tough on crime standpoint in the Latin American Country has won re-election with 85% of the vote. His New Ideas party also won 58 out of the 60 assembly seats in the unicameral legislature. This has brought concerns of a possible one-party state that is not shy to violate human rights.

This steep victory has raised possible election fraud concerns from a president who proclaimed himself to “the world's coolest dictator” although there has been no reports of electoral irregularities.

Bukele has been the legitimate president of El Salvador since 2019, but it hasn’t come without its controversies. When the president sent the Salvadoran Army to the Legislative Assembly in order to coerce the government into approving a multi-million dollar loan, many organizations denounced this action as resembling a coup. Additionally, Bukele’s has tough-on-crime policy has amounted to mass-mistreatment of prisoners who had already lived in poor conditions. For instance, Bukele’s main crime policy – an anti-gang state of emergency – has already led to the imprisonment of 1% of the population.

His re-election raises interest on unequal separation of powers in El Salvador which threaten the country’s democracy. El Salvador has a unicameral legislature which is the main check on the executive branch. However, the legislative branch is often incapable of limiting Bukele, because his New Ideas holds a super-majority.

Judicial accountability is likewise unreliable. In 2020, Bukele dismissed the entire Supreme Court and appointed his own Justices. Bukele rationalized this action as a necessary evil in order to clean up the corruption of the Judicial branch, but neighboring countries have been deeply concerned by this rash action.

Bukele’s tough-on-crime posturing and uninterest in democracy seems to have others in the region interested. Honduras and Guatemala have expressed interest in following a similar model to El Salvador. If Bukele’s next term can deliver on his anti-gang promises, perhaps his model may become adopted by others.

Ecuador: President Noboa Decides to 'Neutralize' Criminal Gangs

Written by: Candace Graupera; Edited by Chloe Baldauf and Luke Wagner

Prosecutor César Suárez was fatally shot on Wednesday in Guayaquil, deemed Ecuador’s most dangerous city. Suárez, known for his involvement in high-profile cases, was targeted while driving.

This month, Mr. Suárez had been investigating an incident during which masked gang members stormed the set of a public Ecuadoran television station, brandishing pistols and what appeared to be sticks of dynamite. The intrusion occurred during a live broadcast on the TC Television network – terrorizing public audiences and prompting the Ecuadoran President Daniel Noboa to assert that his nation had fallen into an "internal armed conflict."

The assault is part of a series of attacks that have rattled Ecuador, such as the reported prison escapes of two prominent narco gang leaders. President Noboa declared a national state of emergency, which suspended the rights of prisoners and suspected gang members. Additionally, the presidential decree identified twenty narco gangs as terrorist groups and ordered the military to "neutralize" these illicit organizations.

The recent escalation of violence in Ecuador has been linked to the prison escapes of two gang leaders, Adolfo Macías and Fabricio Colon Pico. “Los Choneros” – a narco gang led by Macías and that has strong connections to Mexican and Colombian cartels – are vying for control of routes and territory, even within detention facilities where they exert considerable influence.

Suárez was also handling the Metastasis case, involving an Ecuadorian drug lord accused of receiving preferential treatment from various authorities. The murder of Suárez adds to the wave of violence in Ecuador, including the abductions of police officers, following the escape of gang leader José Adolfo Macías Villamar from prison. Macías, associated with the Los Choneros gang, triggered a state of emergency, prompting military intervention in prisons and sparking a series of attacks across the country.

Earlier this month, President Noboa declared a nationwide state of emergency in response to an uptick in organized criminal gang activity across the country. A nighttime curfew has also been instated as a precautionary measure, which remains in place as attorney general Diana Salazar’s office investigates the murder.