The Role of Jamaican Nurses in Health Care Sectors

Staff Writer Angela Pupino explains Jamaican nurses’ central role in healthcare history.

Mary Seacole was in London in 1854 when she heard about a shortage of nurses on the frontlines of the Crimean War. The Jamaican nurse offered her services but was turned away. Some contention remains about whether Seacole was rejected because she was a mixed-race woman or because she did not apply properly, but Seacole regardless navigated her own way to the battlefield. After opening a hotel and caring for soldiers near what is today Kadikoi, Ukraine, Seacole wrote a best-selling autobiography about her experiences travelling the world.

On its face, the story of a Jamaican nurse stepping forward to try and fill a need in the United Kingdom’s healthcare system seems like a relic of the colonial era. But fifty-five years after Jamaica gained its independence, Jamaican nurses are still heading to the United Kingdom. Unlike Mrs. Seacole, they are not being turned away. On the contrary, they are being given job offers that they cannot refuse.

The Caribbean Community and Common Market estimates that between 1996 and 2006, 50,000 nurses left Jamaica to work in other countries. This migration resulted in a loss for Jamaica of $2.2 million dollars in nurse training expenses. According to Janet Coore-Farr, head of the Nurses Association of Jamaica, Jamaica lost around one fifth of its specialized nurses in 2016 alone. The chairman of the University Hospital of the West Indies reports that around half of specialized nurses trained by the hospital are recruited by foreign organizations before they even graduate.

The nursing shortage has had dire consequences for the Jamaican healthcare system. Reports of short-staffed hospitals cancelling surgeries due to a lack of specialized nursing staff appear frequently in Jamaican newspapers. The impacts of the nursing shortage are not limited to any one sector of the healthcare system. According to a UN Development Programme report on Jamaica’s ability to meet the Millennium Development Goals, nursing shortages have adversely impacted Jamaica’s immunization and maternal health clinics. In 2006, the World Health Organization published a report providing evidence of a correlation between density of healthcare workers and population health outcomes.

Decades of nursing migration have caused a sizeable decline in nurses relative to Jamaica’s population. According to the World Bank, Jamaica had 1.65 nurses and midwives per 1,000 people in 2003. By 2008, that number had decreased to 1.08. For comparison, the World Bank listed the average number of nurses and midwives for OECD nations at 7.7 per 1,000 population in 2012. Meanwhile, the demand for nurses in Jamaica is expected to grow as the population ages. The World Bank estimates that the English-speaking Caribbean will need 10,700 more nurses by the year 2025. Nurses are a key component of any healthcare system, and a shortage of this magnitude could leave the nation unprepared to handle disease outbreaks and other public health emergencies. But nurses are also a key component of Jamaican society, often serving on the frontlines of public health provision and education in their communities. Without an adequate number of nurses, these communities will suffer.

Push and Pull Factors in Jamaican Nursing Migration

At its core, Jamaica’s nursing shortage is the product of decades of nursing shortages in the developed world. A rising demand for nurses, due in part to increasingly complex needs of an aging population, has been coupled with a decreasing supply of qualified nurses in many countries. A 2007 study of nurses in the American Midwest region found that 38% of surveyed nurses reported feeling problematic burnout associated with their jobs. Young nurses are even more likely to experience burnout, with almost 44% of nurses under the age of 30 reporting the same level of burnout. The stressful nature of the nursing profession has been compounded by staff shortages, driving more nurses away from nursing. Ironically, the nursing shortage also been exacerbated by a shortage of nurses qualified to teach in nursing schools. Over 75,000 qualified applicants are turned away yearly from US nursing schools because of a shortage of qualified faculty.

As nursing shortages ravaged healthcare systems in places like the United Kingdom, United States, and Canada, these countries began working to attract qualified nurses from other countries. In the case of the United Kingdom, the migration of nurses from other parts of the Commonwealth began with the formation of the National Health Service. A BBC documentary drawing attention to Britain’s black nurses reports that as staff shortages threatened the nascent NHS, thousands of nurses from Britain’s colonized countries stepped in to fill the need. According to a 2017 report by the British parliament, around 1,700 Jamaican medical staff currently work for the NHS.

In the face of these staff shortages, Jamaican nurses are attractive candidates for international recruiters. As part of the English-speaking Caribbean, Jamaican nurses are usually native English speakers. Due to their English fluency, Jamaican nurses passed the National Council Licensure Examination, a test used in the licensing of nurses, at higher rates than other international applications.

What attracts Jamaican nurses to positions abroad? The promise of higher salaries is an important factor. The average starting salary for a nurse in Jamaica is around $8,000 US dollars, and even experienced nurses may only make $20,000. Compare this to the the average starting salary of a registered nurse in the US, which in 2015 was $65,490. And while international medical centers often offer Jamaican-trained nurses lower salaries than they would to graduates of US and UK medical schools, these salaries are still significantly higher than in Jamaica. The World Bank found that only 6% of non-migrant nurses were satisfied with their salaries, compared to 85% of nurses who migrated out of Jamaica.

The Future of Jamaican Nursing

What does Jamaica’s nursing shortage tell us about the modern-day relationships between former colonizers and the formerly colonized world? It tells us that, even in a postcolonial world, relationships between colonizers and the colonized are complex and are still primarily an issue of inequity. The nursing shortage contributes to very real disparities in healthcare quality between Jamaica and many of the nations that are recruiting their nurses. Short-staffed clinics and hospitals and overworked medical staff can negatively impact the quality of life for many Jamaicans.

The migration of Jamaican nurses to other countries in search of better employment opportunities also benefits Jamaica economically, further complicating the relationship between the county and more developed nations.In order to get the most complete picture of Jamaica’s nurses working abroad, it is important to highlight the benefits that working abroad provides to the nurses and their families as well as to the nation as a whole. Surveys of migrating Jamaican nurses have found that those who migrate are considering a number of non-economic factors, including the chance to reunite with family members abroad, access better professional development opportunities, and have a better quality of life overall. Working abroad for higher salaries also allows nurses to send remittances home to their families. Remittances comprise an important part of the Jamaican economy, with an estimated $2 billion in remittances being sent back to the country each year. This money can be used to benefit Jamaican families and communities in a very real way.

How can Jamaica and the countries whose healthcare systems benefit from employing Jamaican nurses work together to reduce the nursing shortage? In response to the shortage, Jamaica has begun employing an international recruitment system of its own. The island is hoping to bring medical personnel from India and Cuba into its healthcare system in order to fill vacant positions. This outcome is ironic: as the developed world continues to lure away Jamaica’s nurses, Jamaica must try to attract its own nursing from elsewhere in the developing world. By recruiting nurses from other developing countries, Jamaica runs the risk of creating nursing shortages elsewhere in the world. Even countries that invite their nurses to find employment abroad are not immune to shortage. Under the 2001–2004 Medium Term Philippines Development Plan, the Philippines trained and actively encouraged its nurses to seek employment overseas. But within a few years of implementing this policy, the Philippines faced a nursing shortage of its own. Relying on the recruitment of nurses from even poorer countries can lead to a cycle of recruitment and shortage that strains healthcare systems across the world.

It is clear that the developed world must also take steps to reduce its dependence on nurses from Jamaica and other developing nations. Jamaican Minister of Health Dr. Christopher Tufton addressed the United Nations in January of 2017 to request the organization’s help in crafting multilateral and bilateral agreements to encourage the developed world to more responsibly manage their need for medical personnel without straining the healthcare systems of other countries. Writing for the Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, nurses Brenda Nevidjon and Jeanette Erickson offer several recommendations for reducing the nursing shortage in the developed world. These recommendations include increasing the number of nurse educators to allow for larger numbers of nursing students in medical schools and implementing a combination of long- and short-term strategies to improve the recruitment and retention of nurses.

When Mary Seacole’s offers to provide medical care for British soldiers injured on the frontlines were rejected, she probably could not have imagined the day when British hospitals would clamor over the opportunity to hire Jamaican nurses. The nursing shortage in Jamaica raises important questions about the future of the Jamaican healthcare sector and the relations between former colonizers and the formerly colonized in today’s postcolonial landscape. Jamaican nurses have been serving the healthcare systems of the United Kingdom and other developed nations for centuries. Now it is time for the developed world to support Jamaica’s healthcare system in return.

Infrastructure is Donald Trump’s Most Popular Policy, But The President Can’t Strike a Deal

Staff Writer Alyssa Savo explores the president’s difficulty achieving effective policy on infrastructure.

“The oath of office I take today is an oath of allegiance to all Americans. For many decades, we’ve enriched foreign industry at the expense of American industry; Subsidized the armies of other countries while allowing for the very sad depletion of our military; We’ve defended other nation’s borders while refusing to defend our own; And spent trillions of dollars overseas while America’s infrastructure has fallen into disrepair and decay.”

Nearly 31 million Americans were listening in to the new president’s inaugural address on a chilly January morning. The speech they heard was unlike any other given by a U.S. president in living memory, calling out a dying nation whose most basic industry and infrastructure were in ruin. “American carnage,” he called it, pointing to the country’s once-famous highways, airports, and bridges that had fallen into disarray. The president went on to assure the audience that under his leadership, the nation would soon embark on the great mission of rebuilding its crumbling infrastructure “with American hands and American labor.”

This was not the usual promise of newly-elected Republican presidents, but it was a familiar refrain from Donald Trump, who had spent over a year on the campaign trail vowing to invest in American infrastructure. In October of 2016, the Trump campaign unveiled a groundbreaking new infrastructure plan: a spending package that would combine private and public investment, clocking in at over $1 trillion dollars, easily eclipsing Hillary Clinton’s $500 billion plan. Donald Trump’s campaign site on infrastructure included a length list of promises, including a “visionary” new transportation system in the tradition of President Dwight Eisenhower, the establishment of new pipelines and coal export facilities, and the creation of thousands of jobs in construction and manufacturing. Such a massive government spending project was major departure from Republican orthodoxy, which had long been averse to any such public spending increases. Just eight years prior, Republicans had staunchly resisted President Barack Obama’s post-recession stimulus proposal that included, among other things, broad investments in infrastructure and transportation. Donald Trump had never been a typical Republican, however, campaigning on a platform based more in populist nationalism that left little room for the fiscal conservatism that had come to characterize the Republican party. Americans recognized this, with polls showing that voters thought of Trump as less conservative than any other Republican presidential nominee in modern history.

From an electoral perspective, Donald Trump had plenty of reason to embrace the infrastructure investment plan. Increased infrastructure spending is popular among Republicans and Democrats alike, and was one of Trump’s most well-received budget proposals earlier this March with a 79 percent approval rating. At the time of his inauguration, 69 percent of Americans believed that President Trump’s pledge to increase infrastructure spending was “very important,” exceeding every other promise that Trump made on the campaign trail. Infrastructure also handily weds the liberal objective of public investment with the conservative goal of job creation and attracted support spanning the political spectrum from liberal economist Paul Krugman to former White House chief strategist Steve Bannon. The proposal also deliberately evoked memories of Dwight Eisenhower’s leadership of the Interstate Highway System, which remains widely celebrated by liberals and conservatives alike decades later (a rare feat). Infrastructure spending would theoretically be an easy sell to both the public and D.C. insiders, with significant amounts of support on the left and the right.

Donald Trump’s advocacy of an infrastructure investment plan also highlighted one of his strongest qualities as a presidential candidate, namely his reputation for deal-making and pragmaticism. Infrastructure has long been a major goal of the Democratic party, pushed repeatedly by President Obama and shot down time and again by congressional Republicans. Trump is no stranger to this fact, and has spoken openly about his goal of cutting an infrastructure deal with Democrats in Congress. Democratic senators representing states that Trump won could be particularly open to the promise of an infrastructure package, aiming to reach out to Trump’s base and bring needed investment to struggling states like Ohio and North Dakota. One New York Times interview showed President Trump beaming at the possibility of an deal, hoping for “tremendous” support from Democrats “desperate” for a win on infrastructure.

Eight months out from his inauguration, however, President Trump has taken little action to begin negotiating an infrastructure investment deal. In May, Trump announced that the White House’s plan was “largely completed” and would be released within two to three weeks if not sooner, but the story was quickly overshadowed as the president moved on to traditional Republican policy goals such as repealing the Affordable Care Act. Trump’s initial appointment of Elaine Chao as Secretary of Transportation was well-received, but other key positions in the department such as the administrators of the Federal Highway Administration and the Federal Railroad Administration have been left empty since Trump took office. Now the president seems more concerned with promoting the Republican party’s tax cut plan, even in the wake of destruction unleashed by Hurricanes Harvey and Irma that necessitates large-scale infrastructure rebuilding.

But even if Donald Trump did have his sights set on an infrastructure negotiations, he would likely face several obstacles on the path to a deal. Even though Trump should have an advantage with Republicans controlling both houses of Congress, his spending plan would likely be a hard sell with conservatives. Congressional Republicans have already spent the last eight years challenging President Obama’s proposals to increase transportation and infrastructure spending, including Obama’s post-recession stimulus package in 2009. Though Trump’s proposed plan focuses far more on private spending and investment than Obama’s, Republican leaders have still been lukewarm at best about the prospects of an infrastructure deal. Speaker of the House Paul Ryan and Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell have been largely silent on the issue, while House Majority Leader Kevin McCarthy has emphasized that he would only a consider an infrastructure plan that did not come with any increases in spending. Congressional Republicans, currently preoccupied with the conservative goal of large-scale tax cuts, are unlikely to provide much help to President Trump on a massive infrastructure spending package.

Trump’s recent negotiations with Democratic leaders on the debt ceiling and DACA point to the possibility that the president could push through infrastructure reform by working on a deal with Democratic leadership. However, this path poses its own difficulties. The president’s current deals could quickly unravel, owing to his impulsiveness and tendency to go back on his word, which raises doubts about the fate of any future negotiations. In addition, Trump’s current infrastructure proposal emphasizes private investment, which would likely face resistance from Democrats who favor a plan based in direct government spending. Though Trump could negotiate a new plan featuring greater public investment, he risks alienating many of the Republicans he would need to cross over and vote with Democrats to pass a bill. Congressional Democrats who were initially optimistic about the possibility of working with the president have also grown more wary in recent months. Ohio Senator Sherrod Brown, once open to negotiating with President Trump in areas they agree on, has expressed fears that the president’s infrastructure plan would empower Wall Street while sacrificing protections for workers and the environment. Trump would have to win over reluctant Democrats by proving that an infrastructure deal will be to the benefit of their own states and not just the current administration’s allies.

The prospects for Donald Trump’s massive infrastructure rebuilding plan seem great, and would likely be met with broad support from both the American public and the chattering class. However, the path to passing such a massive spending plan is far more rocky than the president’s rhetoric seems to indicate. Though Trump prides himself on his deal-making talent, he has yet to to demonstrate the commitment to careful and difficult policy negotiations that a bipartisan infrastructure spending deal would mandate. Striking an agreement between Republicans and Democrats in Congress would require President Trump to walk a fine line between private and public spending, and party priorities are currently focused more on tax cuts and DACA than on infrastructure. As it stands, Trump’s lack of interest in advancing his most popular policy proposal prevents these negotiations from even getting off the ground.

A Post-Truth Era: America’s Agora

Staff Writer Kevin Weil explores President Trump’s tenuous relationship with the truth.

“What people believe prevails over the truth” – Sophocles, The Sons of Aleus

Among the societal preoccupations and political wedge issues that have pervaded American culture, none is perhaps free from the entanglement and securing of the right to openly speak one’s opinion. The right to free speech is one of America’s most cherished and revered principles. It maintains the open marketplace of opinions and ideas that drive our social and political discourse; its role in American society is unrivaled, for it protects the public’s accessibility to the fundamental principles of liberty and equality. And yet, it would appear that this right has recently proven to have drawbacks, namely in facilitating the very divisive social climate that the American people find themselves within in 2017: one preoccupied with racial tension, political polarity and recalcitrant sentiment, misguided accusations of immorality; and the endurance of a social atmosphere void of mutual respect – an actualized culture war that is evolving from a “post-truth” era.

The concept of a “post-truth” era is relatively new in name, but its hallmarks can be identified throughout history. A post-truth era is entirely catalyzed by demagoguery, rhetoric, and an appeal to innate and primal tendencies of human behavior. Certain personalities are predisposed to this behavior; those who establish a Machiavellian public image, whether consciously or unconsciously, utilize traits of egotism and duplicity to garner a popular following based in persuasiveness and potency. Further, a post-truth era’s social and political climate heavily neglect objective fact in order to shape popular opinion. American culture has progressed to a point in that political leaders now have the option to take advantage of the fallibility of man. Espousing lies and false Cassandras to shape public opinion is now a reality. The truth has become blurred and the conflation of a dyadic relationship has integrated itself into political dialogue: the truth becoming a lie, a lie becoming the truth.

A dyadic relationship between truth and falsehoods is not exclusive to these virtues: love and hate, good and evil, light and dark, animus and anima all find universal meaning from their respective dyadic relationships. These ideas would come to be supported by the psychological research of Carl Jung, who observed and recorded these relationships across historical, literary, and artistic mediums. The ancient Greeks, as a matter of fact, were particularly fascinated in assessing the value of dyads, especially wisdom and ignorance throughout human nature. These relationships pervade human nature and exist in various forms. In today’s political landscape though, the concept of “truth” has been taken for granted and handled irresponsibly, ultimately being used to sway public opinion and to consolidate popularity.

The idea of “truth” and the virtue of wisdom has been held in question throughout history, especially during the Classical Greek period. Plato, for instance, describes Socrates’ encounter with a post-truth phenomenon in The Apology. Socrates argues with a politician who claims to be wise and, when Socrates begins challenge his claim, both the politician and several engaged bystanders become angry and hateful of Socrates’ prying. Of course, this is not to say Socrates’ inquisitions was not valid; the ancient Greeks were fond of argument and debate within the agora as a part of their culture. But Plato’s description of this encounter goes beyond a simple disagreement between two individuals; rather, he describes a confliction of virtue – of wisdom and ignorance – that generates greater hostility when compared to a simple difference of opinion.

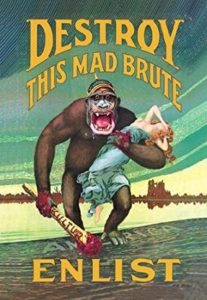

This is seen throughout American history. The freedom to speak and to organize around those with like ideas and opinions has driven political discourse since the drafting of the Constitution. Yet once a faction seizes on a falsehood that people can perceive as truth, positions are entrenched more vehemently and our culture begins to sway and waiver. Factions that have historically advocated for these falsehoods as platforms carry many similarities to America’s current sentiment. The nativist sentiment pushed by the American Party, or the “Know Nothings,” purported ethnically charged lies about Irish and German immigrants; the domination of American culture by wartime propaganda throughout the World Wars that was particularly aimed at the Germans and the Japanese, displayed the government’s ability to take hold of and manipulate popular opinion; and even the fear-mongering sentiment of McCarthyism showed the extent at which government can pursue accusations without proper evidence. How can one say that our current situation is so unique when American culture thrives off of biases and skewed positions?

Interestingly enough, our current situation is unique; though historians can reflect on the past travesties of America’s culture, they are currently disavowing our present circumstances, essentially history repeating itself. And although the past and current sentiments may have been justified through ideas like patriotism and national security, a consensus has been drawn that at present this sentiment is proving a danger to America’s institutions, namely the abuse of the right to free speech. A clear example of this is an interview between then-candidate Donald Trump and conservative talk show host Hugh Hewitt; in this interview, Trump openly lies in asserting that then-President Obama had created the terror organization ISIL, affirming his no-nonsense, “tells-it-like-it-is” branding. Trump has manipulated America’s past sentiment and morphed it into a post-truth phenomenon, modifying it in a way that is impervious to any form of argumentative dialogue or debate, for it only fuels the haste and passions his followers.

To his credit, it would appear Trump’s campaign style depended upon the successful manipulation of mass media outlets like CNN, Fox News, and the New York Times. Whether his un-statesmanlike behavior was a strategic campaigning style or that his blunt statements carried his voting base, the mass media outlets’ coverage of the Trump campaign provided with about $2 billion worth in extended news cycles by February of 2016, despite the Trump campaign only spending about $10 million in advertising. Trump himself, as a prelude to his eventual Presidential run, remarked in the late 1980s that being “a little different, or a little outrageous” attracted the press. He would come to capitalize on this idea of political differentiation from a field of establishment candidates and built his platform that legitimized outrageousness and falsities, eventually manipulating the media to project the message.

And where do we go from here? American political culture is faced with a breach of precedent, accompanied by hyper-partisanship, ideological differences, and divisive rhetoric. Unfortunately, this has engendered an environment in which many organizations and institutions have resorted to restricting free speech as an instinctive measure. In a recent Pew Research Center poll, 40% of Millennials who responded claimed that they were in favor of restricting free speech through government censorship if the speech was considered offensive to minority groups. It’s a natural inclination to silence divisive opinions and ideas through government intervention as well as, more informally, social dismissal. Yet, this is not conducive to American culture for it limits the freedom, equitability, and accessibility to the right to freely speak. If an opinion has proven to be wrong, the open-market of ideas will deem it as so, without need of censorship.

Upon reflection, it is necessary to ask: what does the truth provide us? Plato, for instance, insinuates within his Allegory of the Cave that it is an ideal “form” to strive to achieve. This may hold some validity, but this proposition does not take into account the value of argument and debate, despite this process being integral to ancient Greek culture. John Stuart Mill, however, does write extensively about open dialogue as well as the benefit of free and open discourse in his essay On Liberty. He contends that the advantages of open dialogue is far more beneficial to an individual’s given potential compared to a society of restricted speech or false opinion. Mill writes:

“Men are not more zealous for truth than they often are for error … it [truth] may be extinguished once, twice, or many times, but in the course of ages there will generally be found persons to rediscover it, until some one of its reappearances falls on a time when from favorable circumstances it escapes persecution until it has made such head as to withstand all subsequent attempts to suppress it.”

Mill perceives the looming threat of falsehoods in a society of free and open dialogue, and purports that only time and engaged dialogue can reveal the advantages of free speech. Although this post-truth phenomenon is seemingly void of any logical dialogue, the presence of dissent and opposition is a healthy reaction when effected through a comprehensive dialogue.

In reality, it seems American culture has diverted from Mill’s quintessential society. Racial and ethnic tension, political divisiveness, and an acute lack of empathy pervades our culture, enabled by our social media platforms. Bret Stephens, a New York Times columnist and a recent recipient of the Lowy Institute Media Award, described the social climate in the United States in a recent lecture. He describes that American dialogue and, more particularly, dissenting dialogue is readily toxic in that:

“we fight each other from the safe distance of our separate islands of ideology and identity and listen intently to echoes of ourselves. We take exaggerated and histrionic offense to whatever is said about us. We banish entire lines of thought and attempt to excommunicate all manner of people … without giving them so much as a cursory hearing.”

This is what is allowing America’s post-truth era to flourish. Individuals form and hold opinions and do not challenge people openly and publicly – they limit their dialogue to the social consolidation and anonymity of the internet. The freedom of speech coupled with mass and social media has generated a culture of intense ideological siloing of individuals that do not truly engage and quash false ideas. Consequently, a sizable amount of individuals are left accepting lies and ignorance as truth.

In this present time, the freedom to openly argue and debate is an influential weapon to wield. Its comprehensive, logical, and if used effectively infallible. It is no surprise that it has been utilized in all aspects of public life, for it is the arrow to society’s target. And as new obstacles present themselves, such as the rise of fringe factions like the neo-Nazi party, anti-semitism, racist and bigoted factions, or any faction that is not representative America’s inalienable principles, understanding the value of unrestricted public discourse is monumental.

For leaders that perpetuate a phenomenon in which objective falsehoods, their time in power is — to Mill – ostensibly numbered. These leaders peddle demagogic rhetoric only to have it fall out of the graces of popular opinion soon after. But only the freedom to openly, respectively, and empathetically express dissent to others is how individuals can combat a post-truth phenomenon. Consider former President Kennedy’s inaugural words in the face of today’s post-truth era: “those who foolishly sought power by riding the back of the tiger ended up inside.” President Trump may have modified the political playbook, but it may be accompanied by drawbacks. Trump has interestingly played off of the emotions of Americans rather than objective fact. Emotions are dynamic and volatile; only time will determine Trump’s perception by the public, considering his support, in its entirety, is established off of emotions.

As American culture develops it is invaluable to understand these moments in time. Not only is it crucial to acknowledge that a post-truth society was enabled, and that truth and falsehoods were easily manipulated and conflated, but also how it was facilitated and what were the priming variables. Partisan polarization, ideological consolidation, association based in uniformity rather than diversity, have become symptoms of a post-truth era and should be considered in the future. Freedom of speech, though it appears to have been a major influence in this problem, has also shown to be a powerful way to overcome the natural tendency to trust in human emotion and impulse rather than objective fact. But until American society understand this value, only time will tell if American culture will understand the dangers of a post-truth era.

The Role of the Law of the Sea in the East and South China Sea Arbitration

Guest Writer Oksana Ryjouk analyzes the intersection between international legal precedents and maritime security in the South China Sea.

For years, many of the most disputed debates within the international world have included water. Many people have even questioned whether the next world war will be about water and the shortages humans face, as a whole. To this regard, many international disputes regarding water have surfaced to greater importance, especially with the realization that climate change is impacting the world far greater than was once believed. This climate change trend has sparked what can be considered more drastic measures taken by the neighboring states in the Asian-Pacific region. Japan, China, Taiwan, the Philippines, and the Korean Peninsula are all major states impacted by adverse political and economic effects in the area, and all have disputed their contested areas for centuries. These disputes can be traced back to a time of imperialism and expansion of empires, spanning the Sino-Japanese War of 1894, World War II defeats and Cold War geopolitics, adding complexity to claims over the islands. Whether Japan is losing its fisheries and access to sustainable diet, or to China creating new islands, the coastal states in this region are starting to lack the cooperation they had when economic zones were created. Likewise, sovereignty has also been placated within this economic zones. Thus, the modern day disputes that have risen, especially with the United States pivot towards the region, have concluded a more complex understanding than just legal components of international law, climate change, and economic territorial zones.

A way to solve territorial disputes, linked to political and economic crisis, is to arbitrate between the parties, and in this context, it usually involves an international organization as a mediator. To understand how the arbitration occurs in the Asian-Pacific region, the specific outlines of the Law of the Sea need to be primarily understood within the context of the South China Sea. Most recently, in the Permanent Court of Arbitral Tribunal in The Hague between China and the Philippines, the court clarified many historic rights that have been claimed, that set a precedent for the rest of the South China Sea. The Tribunal stated that under UNCLOS (UN Convention on the Law of the Sea: “there is no legal basis for any Chinese historic rights within the nine-dash line.” This is important because this dashed line (which has also been known as the ten-dash and eleven-dash line), has been claimed by the Republic of China (Taiwan), and thus the People’s Republic of China (China), which was claimed to allow a majority controlled portion of the South China Sea. The difference between this space and another geographic location are based in three factors. First, China has begun to build artificial islands with military-ready landing strips… in an area where there is still legal deliberation occurring for contested area, and claims to land that they do not have. Second, there are four other countries and the territory of Taiwan that are also claiming contested territorial claims to the area, which would definitely lead to more disputes between surrounding fishing, environmental impact and blames, military strategy placement, and more. Third, there are major ecological, environmental, and physical changes that have occurred in the area due to rising populations, state demands to sustain these populations, and unchanging demands per population metric.

The situation in the South China Sea has unduly caused stress on the environment in the area and thus, has created a major problem for the populations of animals, plants, insects, and others in the area. Non-state actors, such as the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) and the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR), have researched and issued statements regarding the environmental impacts of these arbitrations. They claim that “total fish stocks in the South China Sea have been depleted by 70-95 percent since the 1950s and catch rates have declined by 66-75 percent over the last 20 years [even though] The South China Sea is one of the world’s top five most productive fishing zones, accounting for about 12 percent of global fish catch in 2015 [with] more than half of the fishing vessels in the world operat[ing] in these waters, employing around 3.7 million people, and likely many more engaged in illegal, unregulated, and unreported fishing.” This poses an enormous problem for the sustainability of the area, both for the populations of the countries surrounding these waters, and also for the environment.

The populations of the coastal areas in the region have already begun to complain, citing shortages of food, limited diversity of species, and increased water temperatures. A well-known indicator of ocean climates, stress, and temperatures are coral systems. Corals are large bodies of cellular organisms that build on each other, and specifically, in the Asian-Pacific corridor, are known as the ‘Coral Triangle.’ This Triangle is located within the main dispute of the South and East China Sea areas. Already, major coral systems, valued at up to $100 million annually, have begun to die off. Without corals, and consistent monitoring of these systems, which is difficult to conduct with off-shore welling, building of islands, and general overfishing, the economic and sustainable benefits of these creatures will diminish. Coral ecosystem impacts are only the beginning of biological degradation that have impacted the legal system and the people, and is incredibly important to focus on.

Lastly, on the South China Sea relations, the Tribunal, which had previously ruled against Chinese historical rights also created other legal thresholds and jurisprudence. Although young and being developed, the jurisprudence of international courts is moving swiftly in the actions taken by Asian nations. Specifically and most recently, the Tribunal issued a ruling on what qualifies as an island for the first time in its history, saying “To qualify as an island, a geographical feature in its natural condition needs to be able to sustain ‘a stable community of people’ and economic life.” Since the claims made by China in the China-Philippines area were deemed not islands, the Tribunal deemed them rocks, and rocks are incapable of ‘generating their own exclusive economic zone (EEZ).’ Which means, there is no legal basis for any entitlement by China, and by governing maritime law, the long-disputed Spratly Islands chain, or Scarborough Shoal, rather “rocks,” are under Philippine-bound EEZ territory. By declaring the Spratly Islands to be rocks, the Tribunal was able to validate the Philippines’ EEZ territory without delimiting any boundaries, which the Tribunal lacks jurisdiction, and thus, any interferences violates the Philippines’ sovereignty as a nation. These major statements in the maritime law community have ‘made waves’ in terms of understanding what an island is, what a rock is, how geographical settlements can be disputed, and what kind of jurisprudence is created for future Tribunal arbitrations.

Now, understanding the maritime law situation in the South China Sea allows for an understanding in the East China Sea. The East China Sea has a very similar occurrence. This large fishery-dispute within Asian waters have spanned Chinese intervention and claims. Understanding both of these Seas arbitrations is understanding that China is the second-largest economy, and the fastest-growing economy, that needs to support its populations, its economic and military might, and its political power. With 5.3 trillion USD trade dollars annually passing through the South China Sea and East China Sea, 11 billion barrels of oil, 190 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, and with 90% of Middle Eastern fossil fuel exports projected to go to Asia by 2035, it is evident why the trading strengths and force of the East China Sea are imperative not only to China, but Japan and Korea. The economic powerhouses of the region have a lot to lose if international courts do not rule in their favor, and if their military strength is not strong enough to counter their opponents. The power projection from building islands, to increasing fortification, to possible losses in trade deals is monumental. At the moment, the East China Sea legal arbitrations are developing and in dispute; however, further policy actions can be found throughout various non-state organizations and international legal institutions.

The larger impact of the Asian-Pacific region from a non-national security standpoint is imperative in understanding why the situation affects the rest of the world. In a recent Congressional Research Service report, it was strictly defined that “claims of territorial waters and EEZs should be consistent with customary international law of the sea and must therefore, among other things, derive from land features. Claims in the [South China Sea] that are not derived from land features are fundamentally flawed.” This specific report further develops how the legality, or rather illegality, of many nations within the region, not just China, may be found at fault for their actions. The tragedy of the commons incurring due to climate change issues, overfishing, and environmental degradation has caused an even larger concern, and a push towards legal arbitration. Overall, this corridor in the world, which is only a small example of the many regions that are experiencing similar water issues, is of high importance, and one that should not be about competing claims; rather, the South China Sea and the East China Sea arbitration disputes are a larger example about peace and stability in the region.

Donald Trump’s Short-Sighted International Aid Cuts Line the Pockets of Beltway Bandits

Contributing Editor Andrew Fallone elucidates the flaws in Donald Trump’s proposed cuts to USAID.

As we see changes begin to take place in the operations of our government, it is impossible to stay silent as the nation is steered towards disaster, and such is the case in terms of international development. The United States is a global leader in foreign aid, and this is a role which cannot be taken lightly, nor should it be embroiled in short-term partisan conflicts when its ramifications extend far beyond our own borders. Donald Trump has suggested cuts of approximately 31% to the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), which while serving his narrative of saving tax payer dollars, is likely to only result in much greater costs for the nation in the future when we will be forced to spend extravagantly to erase the consequences of this misstep. The majority of Americans mistakenly believe that we spend immense portions of our national budget on foreign aid projects, with most believing we spend upwards of 20% of our budget on aid. Now living in Trump’s America, this widely-held fallacious belief could be some of the reason that USAID found itself on the chopping block. In reality, international aid constitutes less than 1% of national budget. Given its miniscule apportionment of funds compared to other national agencies, any cuts to USAID are more symbolic and politically motivated than actually functional in streamlining government expenditure. The proposed sweeping cuts to USAID would result in more than just a loss of staff and intellect within USAID, but also the entire elimination of the independent U.S. African Development Foundation, U.S. Trade and Development Agency, Overseas Private Investment Corporation, and United States Institute of Peace. The work conducted by these agencies is not simply chafe that can be harmlessly eliminated, for they make a real impact on the lives of people all over the globe. Even outside of USAID, international aid in general is being called into question, with a 35% reduction in funding for the Treasury International Programs. Trump has suggested that the funds freed by spending cuts like those USAID may experience will go to help emphasize our already immense military might. This is counterintuitive if Trump wishes to achieve his stated goal of defeating ISIS, for without the civilian support that fills the gaps left by local government, a similar threat will emerge in the future. Thus, the power wielded by our aid spending cannot be relinquished so quickly.

The soft power that the United States exercises through our aid financing allows us to prevent future conflicts and maintain a role as a global leader. 120 different military generals wrote a letter telling the current administration that they must recognize the importance of this soft power, highlighting that even those who would hypothetically benefit from receiving extra funding cut from USAID mark international aid can attest to the importance of development work abroad as a component of national security. Former Deputy Assistant Administrator for the Middle East at USAID Mona Yacoubian helps elucidate how crucial development aid is to achieving our national security objectives, explaining that security rests on “…the three-legged stool of defense, diplomacy, and development. In this era of complicated security challenges, development, alongside diplomacy, must retain equal footing with defense.” Those in our armed forces also recognize that wars cannot be won with their bullets alone, for as General Joseph Votel, the Commander of U.S. Central Command, was quoted by Foreign Policy to testify to congress, “The military can help to create the necessary conditions; however, there must be concomitant progress in other complementary areas (e.g., reconstruction, humanitarian aid, stabilization, political reconciliation)…Support for these endeavors is vital to our success.” Indeed, once strategic military objectives have been achieved, USAID’s work is crucial to ensuring that a maintained military presence is not necessitated for years to come. In a time when many are already critical of our widespread military involvement abroad, any initiatives which can lessen the need for the deployment of U.S. troops abroad should not be considered ‘wasteful’ spending. The importance of international development aid is further supported by the widely-held belief that following U.S. military involvement in Iraq, the lack of adequate civilian support is what laid the foundation for the formation of the modern Islamic State. As explained succinctly in an article by Washington Post columnist Michael Gerson and former USAID administrator Raj Shah, “Vacuums of leadership are not generally filled by the good guys.” With significant evidence clearly to the contrary, one questions whether Donald Trump’s budget choices result from blind ignorance, or purposeful malice. When speaking about international development aid, Trump told the Washington Post that “I watched as we built schools in Iraq and they’d be blown up. And we’d build another one, and it would get blown up. . . . And yet we can’t build a school in Brooklyn.” This quote illustrates the clear lack of intelligent thought being put into our national security, for while education in Brooklyn is obviously a priority, it cannot supplant aid abroad, because we are not fighting radical extremist terrorism from Brooklyn. Aid works to fill gaps left after military goals have been achieved, building the positive relationships between the United States and civilians abroad that are so crucial to counteracting radical ideologies. If Donald Trump truly wanted to put ‘America first,’ then he would not cut USAID and aggrandize already egregious problems abroad that will only necessitate further spending in the future.

It is clear that Donald Trump’s proposed cuts to USAID serve a larger partisan agenda and scapegoat the already much maligned global poor for no purpose other than easily-condemnable political posturing. Trump has already set a precedent of targeting groups who have little ability to defend themselves, attacking refugees with his first failed and subsequent second revised executive orders on immigration. Trump’s expansion of the ‘Global Gag Rule’ cuts family planning programs abroad, which has real palpable impacts on the lives of people who have no avenue to voice their protest through, and will likely resultin the cutting of malaria and HIV/AIDS prevention programs. Obviously, the global public good is no longer the priority. Refugees find themselves in the sights of Trump’s partisan attacks, for cutting aid to them can allow Trump to parade himself as a price-savvy budget hawk while targeting those who are not afforded the opportunity to create any recourse for such misguided actions. Ill-thought-out actions such as this have drawn criticism from member of Trump’s own party, such as Senator Marco Rubio, who tweeted that “Foreign Aid is not charity. We must make sure it is well spent, but it is less than 1% of budget & critical to our national security.” The despicable targeting of the world’s poorest for political purposes has also drawn the criticism of more than 100 faith leaders from around the country. In a letter to congress, they cite the fact that today we have the most displaced persons living on the planet since the Second World War to decry Trump’s proposed budget cuts, for when the need is so clearly demonstrated we cannot possibly deviate from our mission to promote freedom and human rights if we want to still see ourselves as a ‘city on the hill’ for the rest of the world to follow. Trump’s attacks on USAID are reminiscent of those of Senator Jesse Helm in the 1970s, and they will have similar ramifications. Helm’s attacks increased the reliance of USAID on controversial and problematic private aid contractors, and Trump’s proposed cuts would serve to further increase reliance on the detrimental industry.

International private development contractors profit off of reapportioning segments of money intended to go to international aid and siphoning it directly into their already-overstuffed pockets. Companies whose goal is profit, opposed to a government agency whose goals are more altruistic, cannot possibly compete to achieve the same results in international development, for at the end of the day, their pockets will always come before the stomachs of the global poor. USAID already relies on these “beltway bandits” more than it should, with the top 10 for-profit aid contracting corporations receiving more than $5.8 billion in contracts from 2003-2007. USAID does not have the staff nor the funding to be able to manage all of its projects internally, forcing it to divert funds that could be better spent to aid contractors to be able to achieve some of its goals. Yet, the problem with aid contractors is that they work to achieve very narrow and specific goals, ignoring the larger dilemmas that necessitated the aid in the first place. Indeed, how can we expect companies who profit of the persistence of global problems to have any incentive to solve them? Under president Obama, USAID director Raj Shah worked to move the agency away from its reliance on private contractors, saying that “This agency is no longer satisfied with writing big checks to big contractors and calling it development.” Furthermore, these contractors often struggle to even meet the objectives they are given, building only 8 of 286 schools and 15 of 253 medical centers planned in Afghanistan. Indeed, reliance on aid contractors is significantly problematic for these contractors are monetarily incentivized to falsify their achieved results in order to continue to receive funding, with one group receiving more than $150 million tax-payer dollars for goals that they failed to achieve in reality. Often, especially when considering budget cuts, development contractors are portrayed as a viable option to cut the costs of international aid, for they can more precisely set and achieve specific development goals. Unfortunately, opposed to addressing issues that local populations elect as important to them, or any of the underlying dilemmas that caused the issues in the first place, aid contractors’ goal-setting leads to resources being siphoned to specific issues that are designated by the for-profit organizations as reachable. Indeed, industrial development corporations (IDCs), subsist diverting money intended for the worlds’ neediest into their own pockets, for they rely on subcontracting to accomplish their goals, and at each level more aid funding is lost to profit-motivated contractors rather than furthering any development initiatives. IDC executives take their hefty cut, and then after paying their workers the leftover development funding goes to the companies hired by the IDC, and from there the resulting pittance is paid to local workers to conduct the actual labor of development. This profit-motivated managerialism has colonial roots in the Dutch and British East India Companies, and serves no purpose but to further divide the targets of development from the funds allotted to them, based around the problematic notion that western oversight is necessary to conduct effective development. Trump’s budget cuts for USAID will only increase reliance on IDCs that are erroneously viewed as capable of accomplishing specific objectives more effectively. The belief that for-profit contractors will be able to effectively initiate growth is willfully ignorant, in the face of the ample evidence that they rob increasingly large portions of money from the developing world for projects whose success or lack thereof has no bearing on the paychecks of the IDCs’ CEOs.

It is despicable that CEOs of aid contractors are content to eat luxuriously off money intended for those living on pennies a day, and Donald Trump’s proposed cuts will only further exaggerate the private-aid industrial complex. As USAID experiences further and further cuts, their staff will wane, allowing even less oversight of the aid contracting business which has shown itself to need oversight to prevent gross monetary fraud. Increased reliance on private development contractors does not just have ramifications for civilians abroad, for as Donald Trump sacrifices our nation’s soft power for political objectives, our own citizens will be forced to foot the bill of the inevitable cleanup efforts of the future.

The College Campus and Its Discontents: How Edmund Burke Can Explain the Political Dissonance Between College Campuses and the Trump Phenomenon

Staff Writer Kevin Weil explains the contention between college students and Trump’s base.

It is impossible to overlook the current sentiment being expressed on the American college campus following the 2016 election cycle. Acute anger, frustration, and denial has consumed the campus and its politically cognizant college students while intensifying and even radicalizing their partisan ideologies. It is not, however, outlandish to perceive these campuses as bubbles, who trapped inside, are the newest and youngest minds of the intellectual community that have come to vocalize their dissent of the recent election. The intellectual hubs of the United States – Boston, New York City, Washington D.C., as well as some newly recognized regions – have become entrenched in the mystique of their elite collegiate statuses, and yet seem to remain the most ideologically narrow. The observable campus radicalism on these campuses have come to define the dissonance following the election of President Trump. One can begin to understand how the average college undergraduate perceives the world differently from the “forgotten men and women” of the United States who delivered the election to Donald Trump; but perhaps something is being overlooked, particularly within the mores of a typical millennial college student. In considering the mores of the millennial college student within a campus bubble, the question naturally arises: what is inciting this reaction?

My answer to this question is entirely rooted in Burkean-conservative thought. But before attempting to pinpoint the chief influence that is exciting the mores of millennial undergraduates, one should first note the characteristics of a modern college campus and what kind of environment it engenders. The twenty-first century college campus takes elements of a standard collegiate institution and adds aspects of diversity, tolerance, and secularization – each a hallmark of the millennial generation. It is crucial to understand that the average college campus in 2016 is comprised of millennial students who tend to be both left-leaning in ideology as well as the most vocal and particularly criticalof the 2016 election outcome. Now, within the Trump administration’s first one hundred days, this vocal criticism has intensified with the assistance of social media (Facebook, Twitter, etc.) as well as late-night television, most notably Saturday Night Live, which has recently come to impersonate and satirizePresident Trump with more frequency and playful malice. These factors are substantially intertwined with the mores of the millennial generation; college undergraduates’ frequent use of the internet provides a forum of communication and information exchange (in which they interact with likeminded individuals) and also access to material that discounts oppositional opinions – ultimately reinforces their disposition.

This piece is not an analysis of the uncanny success of the Trump campaign; nor is it one on the unforeseen failure of the Clinton campaign. Rather, its aim is to examine the typical college campus and to understand what, exactly, is driving its discontent and frustration with regard to the recent election. One should not seek the obvious answer – an answer that is validated through disdainful name-calling, stark rejection of dissenting opinions, and emotionally charged positions that compose an intellectually lacking characterization of the Trump administration so far. This discourse only serves to divide the political climate further and contributes little to a constructive dialogue. In actuality, characterizing the Trump administration is such an apprehensive and dismissive fashion only serves to cloud the reasonable mind from understanding the election and the trajectory of United States politics.

Although any millennial undergraduate’s refutation of President Trump’s platform may, on its face, be in reaction to what appears to be rhetoric-driven and partisan policy initiatives, there is a universal and instinctive aura that transcends this campus spiritedness. This intangible and distinctly reactionary sentiment is difficult to understand for we tend to misperceive it as simple anger and frustration. Beyond the messiness of politics, theory provides a clear explanation to why the college campus has become so radical; after all, understanding the theoretical aspects driving the millennial voting bloc’s behavior may reveal questions previously unknown from direct behavioral observation.

As I stated earlier, my ultimate contention in this piece is to assert that the campus sentiment following the election of Donald Trump (and well into his administration) is a backlash premised in conservative thought. It is common to attribute contemporary conservatism to the Republican party; this notion should be discounted, especially within the context this assertion is framed around because this millennial sentiment is, in truth, liberal. Conservatism is not an ideology, but rather a disposition that can be embodied in any movement and reveals itself only in response to a threat. To a millennial college student, the concept of a threat deviates from the typical threats that most conservative strands tend to form their principles against, such as the degradation of tradition, family/community, and faith. Millennial undergraduates, particularly those born in the latter half of the 1990s, hold principles of diversity, tolerance, and secularism as essential aspects of a fulfilling society. They perceive anything contradictory to these principles as a threat to the progressive principles they became politically cognizant under and, also, within which they formed their perception of government and its role in society.

Dealing in absolutes is rather restrictive in any phenomenal examination. Isolating the cause of millennial generation’s reaction is of no exception to this maxim; thus, the millennial backlash against the election of President Trump can be seen as a reaction to the threat to both core progressive beliefs and to establishment politics. Here, I add my conjecture that many moderate Republicans, who make up a smaller portion of millennials but may not hold their bloc’s attributed principles as dear, would also find issue with President Trump’s election. It would be prudent, though, that before assessing the threats to millennial principles, the concept of threats and appropriate reactionary measures are recognized through the founder of modern conservatism: Edmund Burke.

Burkean theory and the conservative disposition can largely be understood from Burke’s ideas within his work “Reflections on the Revolution of France.” In this, he is critical of the French Revolution, believing that the French abused the option to revolt against their monarchical government. It is here Burkean theory manifests; Burke conceives of a society that respects and acknowledges the traditions it was founded upon, preserving these core traditions for posterity. Here, Burke argues that society is, indeed, an intergenerational “social contract” that instills in each generation the principles and traditions of past generations; this is not to say society is to mindlessly follow the traditions of its ancestors, for Burke also contends that “a state without the means of some change is without the means of its conservation.” Burkean theory is largely premised on this concept of adaptability, but also situationalism. To Burke, there is no metaphysical ism that can be construed, abused, and philosophically understood and implemented. Rather, conservative Burkean theory holds the traditions of the past in reference to all unfolding situations, reconciling them with the trends of modernity, and transmitting them for preceding generations.

Understandably, most contemporary conservatives will rebuke the argumentative point that left-leaning millennials, who have come to be major proponents of contemporary progressivism, can be characterized as conservative. One must understand that the characterization of a conservative reaction is entirely different than labeling an entire generation as one that embodies a conservative disposition. It is particularly relevant, though, to recognize the millennial generation as a one of a new political basis – generation that has come to believe social welfare, big government, and aspects of diversity, tolerance, and secularization are all institutions of American society rather than debatable features; that these aspects must be enforced by a centralized authority in order for them to be perceived as legitimate. Therefore, when the argument is made that a nationwide millennial campus reaction is indeed conservative, it implies that these progressive institutions are their traditions and principles.

It is still necessary to understand why millennial undergraduates are having such an adverse conservative reaction to the election on Donald Trump. Of course, it is doubtful that this same reaction would be observed if a mainstream Republican candidate was elected; the issue, then, must be inherent in Trump phenomenon, specifically its refutation of progressive sentiment and its explicit intention of dismantling establishment politics.

A closer look at the progressive sentiments that millennial college students hold as a generational principle will reveal the foundation for their conservative backlash. Implementation of these progressive principles into public life characterizes the progressive movement. And although the modern left carries traces of Wilsonian progressivism, it is currently being cultivated under new trends of diversity, tolerance, and secularization by modern political figures like Barack Obama, Elizabeth Warren, and Bernie Sanders. Each of these figures had a major influence on the 2016 election, primarily for the Democratic Party and its ultimate nomination of Hillary Clinton, and can essentially be seen as epitomized progressive leaders that are praised by millennials. Yet, it is precisely these figures that Donald Trump used to emphasize his own political doctrine of refuting the nation’s public discourse of liberalism.

Millennial undergraduates, nonetheless, are steadfast in affirming their core progressive beliefs; they participate in protests and often use social media as a platform for sharing their political beliefs. It is not uncommon to meet a college undergraduate who is an avid supporter of diversity/minority organizations or, more broadly, one who just supports broad progressive reform. Social media, primarily Twitter, is an advantage to them; they use hashtags (#BlackLivesMatter, #ShePersisted, #Resist, etc.) as a protest tool to grant their shared sentiment legitimacy in the public eye. Twitter, as a whole, has become an interesting forum in the 2016 election cycle being used by both the left and the right, the most notable (and controversial) figure being President Trump.

Perhaps, in some sense, it is here that millennial undergraduates feel threatened for not only are their core beliefs threatened by President Trump’s diametrically opposed policy mandates, but their public platform, too, is being compromised. The normalization of unwelcome ideas on a platform dominated by millennial sentiment can only cause disharmony within the campus bubble – an environment that embodies and champions progressive principles. This concept is rather Burkean in nature; the millennial generation from a young and malleable age has grown to understand social media as a key aspect of modern life. As they age and become politically cognizant they take on their political leanings (which tend to be progressive) in tandem with their use of social media. The mores of the millennial become established and cultivated under the trends of modernity. With the introduction of the Trump phenomenon, their progressive-based forum, as well as the mores, are compromised. Naturally, as Burke would understand it, the inclination to preserve one’s principles is warranted – which gives rise to the current campus atmosphere around the United States.

Establishment politics, which is mutually held as a desirable aspect of centralized government by moderate portions of the left and the right, has also been perceived as a threat by millennials. In a way, the millennial generation’s progressive ideals work in conjunction with establishment politics – in order for one generation to pass on progressive principles to the next, there needs to be an established order. This order has come to be recognized as centralized established politics, or beltway politics. The idea of order and the centralized establishment largely is Cartesian in nature and conflicts with traditional conservatism which holds the family, community, and localities as the main forum to maintain tradition and principle. Cartesian school of thought, established by thinkers like René Descartes and Jean Jacques Rousseau, can be seen as a juxtaposition to contemporary conservatism in that it sees society as a distinct entity from the individual and understands social processes (or centralized government) as a way to serve human ends. Yet, to millennial progressives (and some moderates), order and establishment through a centralized power represent a consistent method to influence society as a whole, for progressivism is inherently forward looking and continually adaptingto trends of modernity.

President Trump’s commandeering of an American populist platform has come to enrage the millennial college campus. His intention disseminate centralized power to localities and rural America are observed by millennials as a both backtracking the Obama administration’s progressive policies and as a threat to any established progressive principles. The Trump campaign branded itself as the anti-establishment movement and ran on the mandate of draining “the swamp.” In essence, the campaign sought to delegitimize establishment politics that has been institutionalized in Washington D.C. and utilized by various progressive movements – like the Woman’s Suffrage Movement and the Civil Rights Movement. Phasing out intermediaries like special interests groups that organize centralized Washington politics becomes a driving force in the Trump campaign and a core issue for his administration. One can imagine the naturally adverse reaction from the millennial generation that has grew in congruence with establishment politics and perceiving its role in society as a positive force. The Obama administration, particularly, can be well understood as the main vehicle of reinforcement, for millennial undergraduates established their partisan and ideological leanings during his campaigns and his two administrative terms. Burkean thought, specifically the intergenerational social contract, would add validity to this claim; the millennial generation has come to believe that establishment politics is principled tradition. They became politically cognizant under establishment politics, believing it is how to effectively implement policy in order to maintain their progressive principles; they are, therefore, in their right to maintain the institution in order to transfer it to the succeeding generations.

The American college campus, therefore, should be seen as having experienced an abrupt conservative backlash. The Trump phenomenon has shaken the foundation of the progressivism and the millennial generation’s principles, even though the overlaps between the Trump platform and progressivism cannot be discounted. For instance, many progressives came to support Senator Bernie Sanders for the Democratic nomination; his platform was similar to Trump’s, specifically in trade policy, special interests, and military intervention overseas. This policy “crossover” between the Trump and Sanders campaign can be explained by another conservative school of thought: paleoconservatism. Paleoconservatism, finds issue with both contemporary establishment Republicans as well as the progressive left Democrats. It detests Republicans for acquiescing on modern issues like lenient immigration policies and promoting a free market. Paleoconservatism advocates for nationalism and isolationism, and restrictions on free trade. Progressivism, interestingly enough, supports similar positions like non-interventionism (although still maintaining a globalist position), and more restrictive trade to benefit the working class. This gives reason to the fact that many of Sanders primary supporters voiced their intentto cast a vote for Trump in the general election. Trump’s platform may be plainly detested by most progressive who believe in opposing policies, but there are observable similarities between both policy preferences of Trump and progressives.

Burke’s ideas of adaptable tradition and its reconciliation with the trend of modernity can attest to the concept of a millennial conservative reaction, though not to the progressive movement as a whole. What should be taken from this analysis of the average college campus and millennial undergraduate is the fact that modern political discourse (that is, up until 2016) has followed a liberal progressive trend. It has not faced a formidable opponent until the rise of Donald Trump who, with his exploitation of rhetoric and demagoguery, was able to overtake establishment politics. Perhaps this signals a newly emerging dynamic in modern political discourse; the ambiguity of the political climate among the divided major parties along with their traditions and principles implies a time strife, reorganization, and an emergence of new leaders. The college campus, although in conservative revolt, may actually be facilitating a reorganization of progressive principles which will come to defend the progressive trends they feel are threatened under a Trump administration. The oppositional dynamic of the intellectual elite and the “forgotten men and women” of America will be put on full display within the next few years and, with it, the contention of how to “Make America Great Again.”

On the Brink of Collapse: The European Union’s Transition as it Strives to Survive

Staff Writer Claire Witherington-Perkins examines the EUs efforts to counteract Euroscepticism.

The recent vote for the United Kingdom (UK) to leave the European Union (EU), commonly called Brexit, was a manifestation of Euroskepticism, a term coined to describe resistance to European integration or involvement in the EU within the UK but which has now spread to other countries. Before the establishment of the EU, the UK, Luxembourg, Belgium, the Netherlands, France, and Germany came together to form the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC), which bound France and Germany’s coal and steel industries together, the two industries absolutely necessary to wage a war, hoping to bring lasting peace to Europe. The ECSC has since expanded to encompass other policies and countries, transforming over time into the EU as it is now. However, the EU is now seen as a failed utopia, and Euroskepticism, encompassing everything from uber-nationalist political parties and their supporters to those providing constructive criticism with a goal of reform, is on the rise in many European countries. The recent struggles the EU has faced began with the acceptance of poorer nations without strong democratic histories, a principle on which the EU was founded, and is culminating in peripheral countries such as Greece, Portugal, Spain, and Italy, which were formerly pro-EU, succumbing to Euroskepticism. Euroskepticism is also rising in countries like Germany and other solvent members of the EU because they now have lacking finances and little willpower to bail out financially struggling members. Euroskepticism is the manifestation of problems in the EU like economic stagnation, the Euro crisis, conflict over migration, and Russian threats and pressures, many of which stem from the much-enlarged, poor, and diverse EU. Overall, the EU is struggling with overall coherence, policy, and solidarity, and while the majority of young people feel they have a European identity, many others feel a European identity is overshadowing and threatening to their national identity and sovereignty. Additionally, there is a tendency to blame Brussels as the head of the EU for problems that may or may not be covered under national responsibilities. Throughout this uncertain period in EU history, there have been many options for the EU: to disband altogether, to remain as it is, to strengthen the binding ties between EU member states, to leave the Euro and keep the EU intact, or have members pick and choose which parts of the union to adhere to. Given all the potential solutions for the EU’s future, the most effective solutions would be to establish a “two-speed Europe”, a pick and choose system.

One factor sparking a call for change in the EU’s operation like a two-speed system is the normalization of far-right political parties in Europe and around the world, marking the first time that far-right groups have been widely popular since World War Two. If far-right parties succeed in key upcoming elections in Europe, they will restrict freedom of movement in the EU, potentially catalyzing the breakup of the Eurozone and the EU as a whole. The upcoming elections in Italy and particularly France have led to uncertainty surrounding the future of the EU and the Euro. The Front National’s Marine Le Pen sees political conflict in Europe as populists, or Euroskeptics, against globalists, or pro-EU thinkers. Le Pen sees the Euro as a political move, rather than a currency, in order to get countries to follow EU protocol and rules. Additionally, Le Pen, claiming that the EU has an authoritarian nature, supports Frexit, the French exit from the EU, if France cannot gain control over their border, currency, sovereignty, economy, and laws (in other words, everything that the EU was created for: linking France and Germany together to prevent another war in Europe). A Le Pen victory could signify the end of the EU, as France was a founding member of the EU. While Le Pen is most certainly the most conservative and controversial candidate in the French election, Francois Fillon, a conservative candidate, is also Euroskeptic, anti-Euro, and anti-migrant. While the French election won’t be finalized until May, the Dutch general election held in March resulted in a win for the ruling liberal party (VVD) with the second most seats going to the far-right party (PVV); however, all other parties have stated that they will not collaborate with PVV to form a government. The UK will also be holding local elections at the beginning of May, and the pro-EU party, the Liberal Democrats, is strong in the polls. Finally, October will mark important elections for the EU as Chancellor Angela Merkel seeks another term and is likely to succeed, but the far-right party AfD is polling well and is likely to take several seats in the Bundestag. AfD is campaigning on a platform that is anti-EU, opposed to funding for Greece and Italy, and anti-migration. The Brexit vote illustrates the importance of the upcoming elections, as any further dissolution could be disastrous for the future of the EU.