Religious Ideology v. Feminism: How Poland’s Growing Feminist Movement is Challenging the Catholic Church

Staff Writer Claire Witherington-Perkins explains the relationship between the Catholic church in Poland and women’s empowerment.

For centuries, Poland was a patriarchal society defined by the Catholic Church, confining women to traditional roles, with the Church and foreign powers reinforcing women’s subordination to men through cultural traditions and customs. While foreign entities occupied Poland, the Polish Church, seen as the mother of Poland, became the only stability and source of resistance in the country, cementing the idea that to be Polish was to be Catholic. Communist attempts to discredit the Church’s authority increasedthe Church’s popularity, prompting citizens to proclaim their faith and follow the Church as a form of resistance to communist rule. Despite the communist government passing legislation encouraging women to work and to alleviate women’s domestic tasks, Poles’ assertion of Catholicism inhibited any real change in gender roles and relations, as the Catholic doctrine confined women to a motherly, domestic role.

Communism’s attempts to redefine women’s roles from traditional patriarchal roles left a legacy of distrust of feminism, and thus, the feminist movement has been slow to emerge since the fall of communism in the 1980s, when Poland received an influx of Western goods. These goods provided an opportunity to introduce contraceptives into society; however, Pope John Paul II allied with pro-life Poles and introduced Catholic family planning in Poland. The post-communist era reinstated the Church’s authority in society, mandating religion classes in schools and priests as teachers. These classes deteriorated women’s status, encouraging domesticity through their rhetoric. Thus, the Church is the dominant moral authority in Poland, formulating the norms of acceptable behavior in politics and society. The Church has been reasserting its presence in Poland at a time when Poles are becoming less religious, and the Church can still influence political debates, as many politicians try to avoid controversial topics like reproductive rights. Competition for political positions and politicians’ fears of losing power reinforces the Church’s influence in politics. Although the Polish Parliament has passed legislation regarding work and maternity, these laws mostly act as a formality and do not impact day-to-day lives. The vastly influential Church, the main hurdle for feminist and women’s rights movements and organizations, is the root of the lack of and opposition to gender equality and reproductive rights, spreading its ideology through its presence in schools and political debates.

European Union

In 2004, when Poland joined the European Union (EU), many Poles within the feminist community had the idea that EU accession would immediately create equality, quieting the feminist movement during the accession process (1997-2004). This process requires adherence to the acquis communautaire, a common set of rules ensuring values such as human rights, equality, or environmental issues embedded in EU legislation. However, this adherence has not assuaged gender discrimination in Poland, especially in the workforce. EU accession has actually reinvigorated religious rhetoric in politics, associating women with motherhood and the nuclear family. Instead of improving women’s reproductive rights, Poland’s EU accession legitimized Polish laws adhering to pro-life ideology. Additionally, EU governing bodies have limited influence on Polish political parties regarding reproductive rights because, legally, the EU cannot intervene on moral values, including abortion. Many feminists in Polandsay that they thought joining the EU would make a large impact on reproductive rights but that they are now uncertain about the future of reproductive rights because the EU has not drastically improved the situation in Poland.

Since Poland joined the EU, the Polish people’s approval of the EU is increasing, but attitudes toward gender equality have experienced limited change. Up to 87% of Poles, the highest percentage in the EU, do not believe that gender equality is a fundamental right, posing a problem for future feminist or women’s rights movements. Many women are unhappy with the state-sponsored provisions for gender equality, and some women have appealed to European legislative and judicial bodies to try to ensure their rights. The European Court of Human Rights ruled against the Polish State in a case where a Polish woman was unable to receive an abortion even though the law entitled her to do so. Furthermore, the Council of Europe stated that women should legally have access to abortion to ensure safety rather than forcing women to have unsafe illegal abortions; however, the EU is unable to take any legislative action regarding abortion. Women’s organizations use “Europeanization”, or becoming more like Western Europe, as an argument for the improvement of women’s rights and access to safe abortion. Furthermore, many Poles emigrate from Poland and move to other European countries with greater gender equality and more open ideas regarding reproductive rights. Currently Poland is at a crossroads: now that it is a member of the EU, it must legally ensure equal rights and oppose discrimination; however, Poland remains one of the most religiously parochial countries in Europe.

Abortion and Reproductive Rights

Abortion was made legal in Poland in 1956 under the Condition of Permissibility of Abortion Act, which overturned the abortion ban in place since 1932. Women from all over Europe traveled to Poland for abortions from 1956 through 1993, a time when the state subsidized abortion. Polish women saw abortion as a fundamental right; however, the Polish government severely restricted abortions in 1993 when it approved the 1993 Family Planning Act. Since then, abortion in Poland is only legal under three conditions: the pregnancy or prospective birth would endanger the mother’s health or life, the fetus has a high risk determined by using prenatal tests, or the pregnancy was the result of a criminal act. This law was seen as a compromise, merging proposed liberal and conservative bills, but it sparked few pro-abortion grassroots movements. The compromise in 1993 established the current tension surrounding every aspect of women’s reproductive rights, but especially those surrounding abortion in Poland today.

As a result of the abortion ban, Poland has a thriving underground abortion market, with an estimated 80,000 to 200,000 illegal abortions and only 200 legal abortions in Poland each year. An illegal abortion in Poland costs between 2,000 and 5,000 PLN ($493.53-$1,233.82), when the average gross salary in Poland is 2,000 PLN ($493.53). Thus, illegal abortions are restricted to wealthy individuals. Illegal abortions are a lucrative industry in Poland: individuals seeking illegal abortions have nowhere else to turn and therefore doctors performing these procedures can charge any price. Thus, pro-choice movements find it challenging to mobilize doctors to their cause, as they are making so much money in the underground abortion market. Even when a woman is legally allowed to receive an abortion, she faces harassment from pro-life groups, and doctors can enact the “conscience clause” that allows pro-life doctors to refuse abortions on moral grounds. To cement the problem, the Polish government does not enforce the legal right to abortion even though its laws state that women in certain situations have the legal right to an abortion. Poland currently has a de facto abortion ban, as many doctors are unwilling or scared to perform legal abortions because they want to avoid stigma and risk for their hospitals or practices. The Church states that this de facto abortion ban is the current social compromise. However, 74% of Poles would rather keep the current legislation than pass a bill proposing a complete ban on abortions, indicating that the majority of the Polish population is in favor of allowing abortions in certain conditions rather than a de facto or complete legal ban.

Many Polish youth are morally opposed to abortions, mainly due to the Church’s influence through the role of priests in education in public schools, calling the fetus or embryo “conceived life” or “conceived child” as rhetoric to discourage abortion. The Church uses these terms to focus on the fetus rather than the mother, which encourages pro-life supporters to think of abortion as the “civilization of death”. While many Poles view abortion as unacceptable, contraception might seem a rational precaution to take for many women; however, that is not the case in reality. Despite the fact that female contraceptives are legal in Poland, the Church exerts such influence that it can affect the availability of these methods. Additionally, many doctors will refuse to prescribe female contraceptives for moral or cultural reasons. Poles have limited literacy concerning contraceptives and different methods of contraception, and women must have awareness and money to find effective, accessible contraceptives. For example, a monthly pill costs six to ten percent of a monthly minimum wage. Thus, only the wealthy and those willing to put in an effort to find contraceptives will have a reliable method of contraception (other than condoms), making reproductive rights a class issue in addition to a gender issue.

Having previously rejected a pro-choice bill aiming to liberalize Poland’s abortion laws, on 8 October 2016, the Polish Parliament rejected a proposed bill that would have been a near-total ban on abortions. Although Poland has one of the most restrictive abortion laws in Europe, the proposed bill, backed by the ruling right wing party, PiS, and the Catholic Church, would have criminalized all abortions, punished women with up to five years in prison and assisting doctors liable for prosecution and prison. Polish women received press around the world for their protests, marches, and strikes. Only fifteen percent of Poles opposed the strike, despite Poland having the lowest acceptance of abortion in Europe. Opponents to the complete abortion ban argue that a complete ban would not only deprive women of the choice of what to do with their own bodies but also would allow an underground market to thrive, which would be dangerous and encourage abortion-seeking Poles to get abortions abroad. Additional criticisms include that women suffering miscarriages could be under criminal suspicion and that the bill would discourage doctors from conducting routine procedures on pregnant women for fear of being accused of facilitating abortion. Women opposing the proposed bill argued that the complete ban was against fundamental reproductive and human rights, threatening to women’s safety and dignity. Both supporters and critics of the bill are unhappy with the current situation of reproductive rights in Poland, leaving the debate at a stalemate.

Conclusion

Poland’s debate itself lacks many key aspects needed to grant women their reproductive rights. There are many aspects of reproductive rights, such as sexual education, access to contraceptives, and hospital conditions (especially maternity wards); however, Poland’s reproductive rights debate focuses on abortion, disregarding larger issues and multiple aspects of reproductive rights. Furthermore, Polish legal language limits social and political discourse for improving reproductive rights because there is no term for reproductive rightsthat is defined as ‘protection of reproductive health and self-determination in reproductive matters.’ In order to make progress on these issues, this crucial term must be defined in order to have meaningful discourse regarding women’s agency.

There are 150-200 women’s groups in Poland, most of which advocate for political and reproductive rights with some intervening in other areas like socio-economic rights. Many women want to have children, but limited access to the labor market inhibits their ability to care for any children they may have. Thus, a solution to this problem is to clear any restrictions women have to the labor market, such as the pay gap, employer gender discrimination, and ideas of domesticity for women, although this would take many years to achieve. Polish feminist movements are actively trying to alter laws, so changing labor restrictions for women is well within these organizations’ goals. To change laws, however, pro-choice women must gain representation in Poland’s political bodies. The main opponent to women’s rights is the Church: the Church claims to protect women’s rights, although many feminists define themselves as Catholic. Much of the debate about Polish feminism concerns how to define it rather than on advocating important women’s issues and grounding these issues in the Polish context. Growing feminist groups and organizations are slowly starting to engage women in projects or activities that increase participation, but this engagement needs to improve. Women need to advocate for themselves and convince other men to advocate for them; however, without a large movement promoting gender equality, Poland will achieve little progress in the area of women’s and reproductive rights.

However, the presence of the Church in Poland creates a difficult atmosphere to obtaining gender equality and reproductive rights in comparison to many secular countries also experiencing a push for equal rights and reproductive rights. To combat these religious ideas confining women to “traditional” or domestic roles will have a few steps. The first step consists of understanding the Church’s rhetoric and rationale concerning their positions on women’s rights and reproductive rights. The second step would be to use the Church’s own rhetoric to push back and argue for gender equality and reproductive rights, starting with less controversial issues and moving onto those issues once the movement has momentum and support. Although these steps are not perfect, they roughly outline the process feminist movements must take in order to combat the rhetoric of the Catholic Church.

The Fate of AGOA

Secretary Deborah Carey analyzes American development efforts in Sub-Saharan Africa.

On May 18th, the US and 39 sub-Saharan African countries will celebrate the 17th anniversary of the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA), the “cornerstone of the trade and investment relationship between the United States and sub-Saharan Africa”. This act has been subject to debate over the years. Is it effective? Should the requirements for African nations be more stringent? Does it invite too much investment in oil exports? This year, a new question has surfaced: Will it be favorable to the Trump administration? President Trump’s recent rejection of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and broader platform favoring bilateral agreements have created uncertainty for existing partnerships, including AGOA.

Overview of AGOA

AGOA was signed by President Clinton in 2000, with the objective of bolstering trade between the U.S. and sub-Saharan Africa. Since then it has been considered the “cornerstone of trade policy” between the U.S. and Africa. There are currently 38 beneficiaries of AGOA, which are able to import 6,500 different products into the U.S. duty-free. Each country benefits differently. Nigeria alone accounted for 32% of AGOA trade in 2013, but other smaller nations and industries are scaling up to tap into U.S. markets. Throughout its implementation, there have been multiple reviews of the program. A performance overview was completed by the US Trade Representative in 2014, before President Obama led the U.S.-Africa Business Summit. Overall, they report that both the U.S. and Africa (as an aggregation of all beneficiaries) have benefitted from the partnership. The highest years for trade were 2008 and 2009, before the global slowdown resulting from the 2008 recession. Over time, a trade deficit (for the U.S.) has resulted, as more African industries tap into the benefits of duty-free exports. This report, and subsequent statements by African leaders, also highlight the existing challenges in the agreement. Most prominent among these are the rules of origin and product list.

Existing Challenges of AGOA

The existing Rules of Origin for AGOA state that a country must add 35 percent value to a good in the benefitting country for that good to enter U.S. markets tariff-free. This is a very high standard for smaller countries that may be producing one item in a large, global supply chain. As a result, one of the major criticisms of AGOA is the indirect manner that it incentivizes petroleum exports. Petroleum products, unlike manufactures, easily qualify under the Rules of Origin. Policymakers in the U.S. and Africa have been developing methods to mitigate this issue. The African Union’s “AGOA Forum” began in 2002, for nations to share ideas and strategies to bolster their industries and benefit from more duty-free products. Some countries have developed individual-country strategies, and favor industries—like textiles—that could qualify for AGOA with the construction of factories.

The U.S. has been partnering on diversification projects to diminish the rules of origin barrier. USAID’s “Trade and Investment Hubs” were created to assist countries in Africa to organize themselves around AGOA. In certain countries, such as Kenya, AGOA has inspired the development of “Export Processing Zones” (EPZ) that build-up infant industries. Richard Kamajugo of TradeMark East Africa underlines the importance of these endeavors: “Repealing the Act would wipe out the EPZ sub-sector that employs about 40,000 Kenyans, and greatly reduce trade as textile and apparel products account for about 80 per cent of Kenya’s total exports to the US.” When renewal was being discussed, scholars suggested the rules of origin be adapted to encourage regional integration. For example, by stating that products could benefit from duty-free entry if a region—like East Africa—contributed 35 percent value to a good collectively, private companies and governments in the region would direct supply chains to include regional counterparts. This suggestion was never operationalized, but remains a leading idea for the 2025 renewal.

The product list has also been a point of contention, and alternative strategies are not as flexible. While AGOA offers 6,500 products, many agricultural products that are essential to countries such as Tanzania—whose agricultural sector accounts for 80 percent of GDP— do not qualify. Sugar and groundnuts are at the top of this list, and remained excluded even after the renewal of the act. U.S. agricultural subsidies are rumored to be the underlying cause for exclusion of “import sensitive products,” defined as U.S. products that are “susceptible to competition from imports from other country suppliers”. Trade ministers of many AGOA beneficiary countries have lamented the exclusion of these products, but the US has not conceded.

Politics of AGOA

U.S.-African economic policy has been uncharacteristically bipartisan. President Bush quadrupled aid to Africa during his administration, and Obama has introduced specific initiatives such as PEPFAR, Power Africa, and Trade Africa throughout his two terms. When the AGOA renewal act passed Congress, it was attached to a larger act– the Trade Preferences Extension Act of 2015–which included Trade Adjustment Assistance (TAA) to mitigate the costs to workers affected by trade policies. Democrats had initially disputed the TAA on a stand-alone act, but with AGOA included, the Trade Preferences Extension Act of 2015 passed in the House of Representatives, 387-32 and Senate, 97-1.

With its highly bipartisan nature and remaining 8-year lifespan before renewal, policy analysts had minimal apprehension that AGOA would be questioned by the new Administration. However The New York Times recently obtained a list of “Africa-related questions” that were sent to experts at the State Department. One of the many inquiries included AGOA. The Administration asked: “Most of AGOA imports are petroleum products, with the benefits going to national oil companies, why do we support that massive benefit to corrupt regimes?” Analysts, such as Witney Schneidman of Brookings Institute, are now apprehensive about AGOA’s future. Schneidman contends “AGOA could easily be the first [trade] casualty under Trump.” Analysts, investors, policy-makers, and trade ministers alike are conspiring—what would the U.S.-Africa trade partnership look like without AGOA?

Impact if Ended

The impact of AGOA has exceeded the statistics of trade balances. Many government programs, private initiatives, and factories have been constructed around AGOA’s existence, since it creates demand for African imports in the U.S. One of the largest socio-economic contributions has been the inclusion of women. Women have been employed in regions where they had minimal involvement in the formalized economy. The existence of AGOA also increased investor confidence in Africa, which has led to both public-private partnerships with government enterprises and greater amounts of foreign-direct investment (FDI).

If tariffs toward AGOA-qualifying products are re-instated, these smaller-scale industries like clothing factories will not be able to compete with large corporations. Some analysts believe that investors, who have observed the market potential in Africa through AGOA programming, will fill in the gap. Others contend that China or the European Union will offer trade promotion programs in the absence of AGOA. Regardless of this speculation, the objective evaluations of AGOA have demonstrated the positive effects of its implementation. Economies in Africa would survive in the absence of AGOA, but trust between the benefitting nations and the U.S. would undoubtedly deteriorate.

Conclusion

Policy-makers and representatives on both sides of the political aisle should vocalize their support for AGOA preemptively, before the fears of AGOA revocation materialize. Those benefiting from AGOA in Africa and supporting its implementation in the US should specify the unique qualities of this U.S-African partnership, so it will be evaluated alone. Lumping AGOA together with other seemingly ineffective trade policies would be a mistake. While AGOA may not be the long-term policy prescription that underlines all U.S.-African trade policy, its benefits have incited the creation of many industries across the continent. The U.S. has undoubtedly benefitted from this multilateral partnership, especially in terms of economic growth and strengthened relationships with African governments. As we look forward to a more fair, growing global economy, Africa must be included; AGOA has facilitated the beginning of what could be a mutually prosperous future for the U.S. and sub-Saharan Africa alike.

Building Influence: Chinese Infrastructure Investment in Latin America

Staff Writer Gretchen Cloutier explores China’s growing influence in Latin America through development projects.

As China’s economic power grows, the Asian giant is extending its reach around the globe. While the country has maintained strong economic ties with Africa since the early 2000s, it has also recently ramped up trade and investment in Latin America. Chinese president Xi Jinping has agreed to double bilateral trade with the region to $500 billion and increase investment to $250 billion over the next decade, according to various deals signed with Latin American countries in 2015. Currently, China is the largest trade partner of three of the leading economies in the region: Brazil, Chile, and Peru. These countries, along with the rest of Latin America, mostly export primary goods and natural resources; copper, iron, oil, and soybeans account for 75 percent of the region’s exports to China. In addition to trade and investment, Chinese loans to the region have also increased from $7 billion in 2012 to $29 billion in 2015.

This investment in Latin America often comes in the form of large infrastructure projects aimed at improving transportation and better connecting the region to lower costs for Chinese imports. As the U.S. is turning its back on relations and trade with Latin America, most prominently exemplified by protectionist calls to end NAFTA and thus free trade with Mexico, China has recognized an opportunity to supplant the U.S. as the extra-regional hegemon. However, this is not due to China’s goodwill and altruism towards the region, but rather an opportunity to control global trade flows through Chinese owned transportation links, and reduce costs of trade to Asia. This is an ambitious goal, and although China has made promises of increased investment and signed deals for large infrastructure projects, it is uncertain if the plans will actually come to fruition.

Considering China’s own domestic politics, it is no surprise that the country favors trade and investment with left-leaning Latin American nations. The former Kirchner administration in Argentina had several deals with China, including plans for a nuclear plant, a satellite tracking station, and a $1 billioncontract to buy Chinese fighter jets and maritime patrol vessels. When current center-right president Macri came into office, he said the deals made under Kirchner would be reviewed and may face rejection, however after five months of internal review, the Argentine government successfully ratified the contracts. China has also loaned $65 billion to Venezuela since 2007, more than any other country in the region. China has a growing need for energy, and Venezuela mainly pays back the loans with oil. However, the current economic crisis in Venezuela could mean that the country may not be able to supply enough oil to China or pay back the loans, and so China announced in late 2016 that it would no longer issue new loans to Venezuela.

Chinese loans and investment are particularly appealing to Latin American countries since they rarely come with political and economic conditions or other requirements, such as implementing austerity of structural adjustment programs. Unlike loans from Western international institutions such as the IMF, Chinese loans have no (apparent) strings attached. Following the Latin American debt crisis of the 1980s, countries that sought relief from the IMF were required to implement structural adjustment policies that imposed austerity measures as a condition of the loans. This resulted in a “lost decade”of economic growth for the region, during which living standards and growth both plummeted. Considering this history with lenders from Western-dominated international organizations, China has found the ideal opportunity to shape Latin America for itself by investing in infrastructure, and, in return, gaining cheap access to the primary and natural resources needed for its booming population and industry sector. Two examples of the largest infrastructure projects currently proposed in Latin America are the Nicaraguan Canal and the Twin Ocean Railway.

Nicaraguan Canal

The Nicaraguan Canal, approved by the government in 2014 with a goal date of completion in 2020, is China’s alternative to the historically U.S.-controlled Panama Canal. The proposed design would stretch 178 miles between the Atlantic to the Pacific Oceans, running across the southern portion of the country, through Lake Nicaragua. It is estimated to cost $50 billion, and Chinese businessman Wang Jing (who owns HKND, the company responsible for developing and building the Nicaraguan Canal) is the only known investor in the project.

Photo: The Guardian

It remains unclear whether or not the Chinese government is directly involved in the planning or implementation of the project. Further complicating matters is Nicaragua’s diplomatic recognition of Taiwanese independence. Every Central American country, excluding Costa Rica, is politically aligned with Taiwan. However, China refuses formal diplomatic ties with any country that recognizes the island as a separate nation. But Taiwan has little to offer Central America, and as China’s economic and political power grows, Nicaragua and its neighbors are likely to shift diplomatic ties to the mainland.

Regardless of the Chinese government’s involvement, the current project is facing setbacks due to Wang’s reported loss of 85 percent of his personal wealth in a stock market crash, which he was using to fund the canal. Additionally, the construction of the canal has faced scrutiny and backlash for its effects on the communities in the surrounding area. It is estimated that about 30,000 people will be displaced due to construction of the canal. HKND has a compensation budget of $300-$400 million, or up to $13,300 for each displaced person. This has not stopped opposition from affected communities, however, and the last two years have seen more than 80 protests against the Nicaraguan government and HKND. These demonstrations have occasionally turned violent, and there have also been reports of arbitrary detainment of protesters. Additionally, concerns have been raised over the environmental impact of the project, including the pollution of Lake Nicaragua, the largest source of fresh water in Central America, which currently supplies water to over 80,000 Nicaraguans.

The construction of a Nicaraguan Canal would give China access to a shipping route across the geopolitically strategic isthmus without having to pass through the Panama Canal. This would lower costs dramatically for Chinese imports, since tariffs and fees for trade through the Panama Canal have tripled over the past five years. It would also give China unprecedented access to the region, with control over how both their imports and exports are traded. Like the revenue the U.S. gained from the Panama Canal, China, or at least the overseeing company HKND, could also profit from other nations paying fees to ship goods through the canal. Nicaragua, too, would benefit economically from increased trade in the region and probable shared profits with China.

While the canal is likely to be economically advantageous for both countries, its environmental and social impact could prove insurmountable. The construction has already faced setbacks due to environmental concerns, and, amid questions about funding, the Nicaraguan canal seems increasingly unlikely, at least in the near future. There has not been much additional construction since ceremoniously breaking ground in 2014.

Twin Ocean Railway

Another ambitious project proposed by China is a transcontinental railway stretching from Brazil’s Atlantic coast to Peru’s Pacific coast. As with the Nicaraguan canal, this railway would facilitate movement of goods and greatly reduce trading costs for China. There are two possible routes for the railroad: one running directly from Brazil to Peru along a northern corridor, and one that passes through Bolivia further to the south. The latter, dubbed the Twin Ocean Railway, follows a more direct route and would cost about $13.5 billion to build, stretching over about 3,700km. The former is estimated at an untenable $60 billion, and would be over 1,000km longer, measuring 5,000km from start to finish. If the project moves forward, it is likely to be built along the more feasible Twin Ocean Railway corridor.

Photo from: Inter American Dialogue

This marks a win for Bolivia, who has been in discussions with China, Peru, and Brazil about being included along the route since 2014, following the signing of a Memorandum of Understanding creating a trilateral working group on the railway that did not include Bolivia. The landlocked country of Bolivia, which has the lowest GDP per capita in South America, has been looking for a way to access the sea since Chile annexed part of its territory on the Pacific coast in a war during the 1870s. The opportunity for Bolivia to once again be connected to seaports via a major trade-based railway could provide a much-needed boost to the economy.

Like the Nicaraguan Canal, the railway project has also been met with criticisms of possible environmental degradation and threats to local communities. Some of the route passes through delicate Amazon ecosystems, and it is projected to expose up to 600 remote indigenous communities that have never previously had contact with other societies. Current Peruvian president Pedro Pablo Kuzynski has also raised concerns that the railroad will be too environmentally harmful to build.

Looking Ahead

The Nicaraguan Canal and the Twin Ocean Railway are two impressive megaprojects, which, if completed, would underscore China’s economic influence abroad, and help to further cement its role as a global economic power. However, both projects are far from completion. In addition to their environmental and community impact concerns—which could halt the projects in and of themselves—many questions have been raised about their economic feasibility and long-term success, especially given China’s track record with similar endeavors in the region.

The Twin Ocean Railway’s aims are very similar to those of the InterOceanicatranscontinental highway, which also incorporated Brazil. The project began in 2006, however it was never fully completed, and the parts that were finished are not entirely structurally sound. Today, it remains a collection of unfinished, damaged, or impassable sections of highway, with no further construction or completion date in sight. Another Chinese company signed a contract with Brazil in 2011 to build a soy processing plant valued at $2 billion; however the proposed project site remains an empty field. Plans for a different railroad to be built by a Chinese company in Colombia in 2011 never materialized, along with another train project that failed in Venezuela. Given China’s history with these other infrastructure projects, it is entirely possible that the Nicaraguan Canal and the Twin Ocean Railway could end up in a similar situation – never completed or, at best, only partially built and then abandoned.

In addition to the projects that were never finished, other contracts have been pulled due to allegations of corruption between host governments and China. A rail project worth $3.7 billion slated for Mexico in 2014 was terminated after a public outcry due to evidence that the deal benefitted allies of Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto. Additionally, a recent scandal in Bolivia revealed that the government awarded almost $500 million in no-bid contracts to a single Chinese company, raising concerns about unlawful special privileges. China’s record of not completing projects or engaging in shady contracts could sour relations with the region and foment public skepticism about foreign infrastructure investment, deterring future opportunities for China to grow its economic influence and for Latin America to develop valuable infrastructure and trade links.

Investment in large infrastructure projects in Latin America could be monumental for China’s economic influence and ever-expanding soft power, while at the same time offering sizeable benefits to many Latin American economies. However, Chinese firms must overcome their previous shortcomings and actually make progress on constructing these projects in a socially and environmentally responsible manner. Transcontinental trade and transportation links are largely missing from the region, and these proposed projects would provide much needed connections not only among neighbors, but also to Asia and the rest of the world.

Russian Aggression and the Annexation of Crimea

Guest Writer Daniel Lynam explores policy responses to Russian aggression in Ukraine.

Following the end of the Cold War and the subsequent collapse of the Soviet Union, power dynamics on the Eurasian continent were reshaped by expansions of Western institutions, such as the European Union (EU) and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). These expansions have strongly contributed to the current state of tensions between the US (and the EU) and Russia. Russia, under the leadership of Vladimir Putin, is attempting to restructure the balance of power on the continent. A restructuring of power dynamics on the European continent is seen as necessary by the Kremlin to maintain their territorial sovereignty. This is on display in conflicts in Ukraine such as the annexation of Crimea in March 2014 and military buildups along Russia’s Western border. The current US policy towards Russian aggression includes raising the cost for Russia for its actions with the goal of regime change and supporting US allies in Eastern Europe.

Historical Background

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) was forged in 1949 to ensure a US commitment to the security of the European continent post WWII and in response the rise of the Soviet Union. The Alliance was formed to ensure a sharing of burden would occur, and that the European nations would too be responsible for their defense in cooperation with the United States. The Soviet Union countered NATO with its own, similar arrangement, the Warsaw Pact between Russia and the communist states in Eastern Europe.

Andrew T. Wolff best describes the source of current Russian aggression as stemming from two historical contexts: a) Russia’s tradition of geopolitical emphasis and worldview and b) a strong disagreement over a 1990 “no expansion promise” made between Russian Prime Minister Mikhail Gorbachev and US Secretary of State James Baker.

Russia has long held a long-standing tradition of approaching the world through a geopolitical standpoint. Russia places an emphasis, above all else, on its own territorial sovereignty and maintaining a relative sphere of influence. This ideology can be seen throughout Russia’s centuries of history as an expansionist empire; some might even argue that this “empire mindset” has still not subsided under the new post-Westphalian state order. This territorial sovereignty is exerted by the ability of the Kremlin to influence politics of that area through political, economic, and social pressures.

The expansion of the EU and NATO, two organizations which deliberately elected to leave Russia out of their membership and operations for many years, pose, for Russia, a threat to its territorial sovereignty as well as its sphere of influence in Eastern Europe by promoting ideals and reform policies not in line with Putin’s administration. Due to the close ties of ethnic Russians across countries like Ukraine, economic and political success there may serve as a ‘spark’ leading to a call for reform in Russia itself—this poses a potential threat to Putin’s control over the country. While some might point to the strong favorability of the Russian leader in the polls, it is important to remember that Putin is looking towards his long-term placement. Should the Russian economy be struck again by recession or depression, that favorability will quickly turn into unfavorability as Russians who were simply content may no longer have a source of income nor food to put on their table.

On a similar note, the 1990 informal agreement between the US and Russia supposedly stated that in exchange for cooperation on a peacefully reunified Germany, NATO would not expand past East Germany. The breakdown comes in interpreting what this agreement actually meant. For the Kremlin, it meant NATO membership would not extend past East Germany, which it did. NATO’s first expansion was in 1999 with the addition of Poland, Hungary, and the Czech Republic into the alliance and has since grown to 28 members. According to a high ranking NATO official, the US and NATO understood this agreement to mean no NATO-deployed troops or bases would be stationed beyond East Germany, which there has not been until after the 2014 annexation of Crimea.

Ultimately, Russia’s interest does not actually lie in the Crimea, but rather the annexation can be seen as an attempt to destabilize the Ukrainian government which was seeking closer ties with the European Union. The government was on the eve of signing a EU-Ukrainian agreement, granting Ukraine access to the EU common market and a push forward on the needle towards accession. Keeping Ukraine from fully integrating with the ‘west’ is of utmost importance for the Kremlin to ensure its sphere of influence remains somewhat intact. This type of power move can also be seen in Georgia, where Russia invaded South Ossetia in 2008 following talks of Georgia looking to join NATO. While Georgia’s NATO aspiration was not the immediate trigger, it intensified relations which ultimately broke down with military build-ups following the downing of a Georgian unmanned drone.

Current US Policy

The current US policy in countering Russian aggression, namely the 2014 annexation of the Crimea and rebel activity in Eastern Ukraine is best described by Steven Pifer, a Senior Fellow at Brookings, in a testimony to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. Pifer broke breaks down the current US response into three sections:

“I. Bolster the Ukrainian Government

II. Reassure NATO allies of the US commitment to defend against Russian aggression

III. Penalize Russia with the objective of promoting a change in Russian policy”

These three aspects of the US’s strategy, in practice, seek to try to increase the cost of aggression for Russia both through sanctions and increased military support of our allies.

US efforts to bolster the Ukrainian government have been accomplished through disbursements of foreign operations assistance with US$513,502,000 budgeted for 2016, up from US$334,198,000 in 2015. These funds overwhelmingly went to support ‘Economic Development’, with the second largest spending category being ‘Peace and Security,’ which includes providing material support and training to Ukrainian troops. These efforts are meant to help sustain the Ukrainian government against opposition forces and help it fund programs to continue to develop the country economically and socially.

In reassuring NATO allies of the US’s commitment against Russian aggression, the US has pledged both support and weapons. The 2015 European Reassurance Initiative saw the Baltic states each receiving over US$30 million each in equipment to bolster their defense efforts as well as dramatic increases of US Foreign Military Assistance being pledged to these nations as well. The US is currently constructing a second anti-ballistic missile station in Poland in order to complete a so-called “European ballistic missile shield.”

During NATO’s 2016 Summit in Warsaw, President Obama announced the stationing of 1000 US troops throughout Eastern Europe, namely Poland and the Baltic states. While 1000 troops offer Europe minimal, if any, tactical advantage, it is moves like these that NATO sees as key to maintaining the alliance. Should an invasion occur into any of these nations, not only will the invaded nation’s troops be attacked, but so will the US troops, directly forcing the US into the conflict. The theory goes that now the US will have no choice but to pursue full engagement after attacks on their own troops.

While these moves have reassured many US allies, they do pose a very real risk of being interpreted by Russia as encroachment and escalation on its border. Without proper channels of communication and a clear understanding between the two parties, these troop movements may be countered by similar build-ups by Russian troops. This can lead to a continuous cycle of build-up by both sides in response to one another.

A key part of the US response to Russian aggression has been so-called “smart sanctions” which target individuals the US has identified as playing a role in guiding and execution Russian aggression in Ukraine and the Crimea. These sanctions are intended to increase the personal, economic, and diplomatic cost of Russian aggression. Sanctions range from freezing of financial assets to restrictions on travel for these individuals. Additional sanctions imposed in partnership with the EU and NATO members a) restrict access of state-owned enterprises to western markets, b) embargo oil production and exploration equipment exports to Russia, and c) embargo military good exports to Russia. The ultimate goal of the sanctions is to force a regime change through external pressure on the regime itself as well as pressure the economically-affected population.

While the Russian economy has been in an economic downturn since 2014, credit may not be fully placed on the sanctions regime, but rather on a global downturn in oil prices. The Russian economy relies extensively on oil exports with minimal diversification. The global downturn in oil prices as directly impacted the economy and the value of the Russian ruble. The sanctions regime has further hampered the recession by limiting the country’s access to credit, meaning it has limited sources of finance. With the recent OPEC agreement to cut production, it will be a true test of the strength of the sanctions regime and how much it will prohibit the economy from recovering fully.

Concluding Remarks

The current conflict in Ukraine is a symptom of wider Russian aggression. These moves, unilaterally executed by Putin, can be viewed as a response to long-term ‘encroachment’ of western organizations like the EU and NATO. These organizations which explicitly do not include Russia (although attempts have been made for more bilateral cooperation) pose threats to what Russia perceives to be its territorial sovereignty and its sphere of influence. Russian moves can be seen to attempt to destabilize the international systems set up by Western powers.

Many politicians and pundits like to talk of a “Russian reset” in which the US (and other Western powers) would attempt to reharmonize relations with Russia and start with a blank slate, of sorts. I can appreciate the sentiment of this approach and for sure, so does Donald Trump. However, I think it’s a folly. A fundamental basis of international relations is the idea of the “long game,” states and actors are always aware of how their actions affect their long-term status, credibility, and survival. The same concept can be applied in a backwards looking manor; it is laughable to think a state will forget previous actions and threats. Rather, I would argue, Trump and other western leaders should look to rebuild relations with Russia fully embracing our past and current clashes. A relationship with Russia should be folded into institutions where the Kremlin can have an equal seat at the table and reassure itself that any moves executed by Western powers does not pose a threat to Russian sovereignty. This is key if any successful and productive relationship with Russia is to move forward.

On the same note, we need to reemphasize it is never okay to sit idly by or fail to respond to aggressive moves on behalf of Russia that threatens sovereignty of other nations. Maintaining sovereignty of all nations is paramount to US security. If we don’t defend others, who would defend us should the day come. That’s why Donald Trump should continue the US’s trifold policy, until otherwise warranted, of bolstering support militarily and economically of Ukraine and its Eastern European allies as well as attempting to usher a regime change through sanctions.

The Case for the Iraq War

Guest Writer Robert Rosamelia looks at past and present American attempts at nation building.

“Nation-building” is often considered a loaded term in our modern lexicon that sets political pundits and experts alike off on riffs and rants that coalesce around how it has been done incorrectly. Talk of the continuing instability in post-Cold War attempts to assist in the emergence of democratic states in Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya, and Syria dominates the conversation surrounding nation-building. This stigma suggests that nation-building is nearly always a recipe for disaster undertaken with foolish expectations in mind for the host nation. However, nation-building can be done with great success—exemplified no better than the postwar reconstruction of Germany and Japan—and carries with it lessons to be learned for future U.S. foreign policy initiatives. In this article, I will discuss three major points about U.S. nation-building efforts in Germany and Japan, the failure to emulate those efforts during the 2003 invasion of Iraq, and how the situation in Iraq can still be improved and serve as a point of improvement:

Planning for the occupations of Germany and Japan was meticulous, whereas the Iraqi plan was undercut by a lack of consensus. Advanced planning for the reconstruction of Germany and Japan began before World War II had even ended. This comprehensive approach allowed the U.S. to create hierarchical and sensible command structures, and American generals were cautious to revert power back to the postwar nations. Iraq’s management was far less detail-oriented. A failure to understand cultural and economic intricacies undoubtedly caused tensions between different religious and ethnic groups to spiral into intense struggles that threaten the stability of the country to this day.

A sense of national identity in Germany and Japan served as a benefit to the occupation. The relatively singular cultures of German and Japanese nationals benefitted American planners by only having to consider each culture on its own. Economic and governmental stability were the major focal points of the U.S. nation-building effort after WWII. In Iraq, the U.S. occupation turned chaotic rather quickly due to the neglect of internecine struggles between various ethnic and religious groups. Because there was no singular Iraqi identity, failure to acknowledge these social hierarchies ultimately fostered an environment where open hostility could not be prevented.

There is still a means of achieving Iraqi stability, but the window is closing. As Iraq is mired by internal conflict, a glimmer of hope remains from the examples of Germany and Japan. America’s role as an advisory power may still serve to mediate discussion between different swathes of Iraqi culture, and complete detachment from their political sphere should be weighed by their readiness to govern. Lessons in planning and execution from Germany and Japan should dictate future U.S. policy, and Iraq now serves as a benchmark for improvement for future nation-building efforts.

Nation-building, as a general term, is often interpreted as the occupation and reconstruction of one nation—the host nation—by another with the end goal of making the host country resemble the occupying nation. In the United States, this definition is often associated with the effort undertaken by the U.S. to democratize the dictatorship led by Saddam Hussein in the aftermath of the 2003 invasion. The lack of anticipation of cultural and economic challenges created a stigma that nation-building is nearly always a recipe for disaster undertaken with foolish expectations in mind. However, nation-building can be done with great success, exemplified no better than the postwar reconstruction of Germany and Japan. American generals overseeing the postwar reconstruction of Germany and Japan had a detailed command structure in place working in tandem with experts on the host countries; the absence of familiarity with Iraqi political culture would hobble American attempts at nation-building after the 2003 invasion just as the proficiency of German and Japanese political culture had benefitted the American proconsuls in the aftermath of World War II. In addition to the rigidly planned and long-spanning implementation of nation-building efforts in Germany and Japan, the homogenous cultural and societal trends in the host countries also served as a boon to U.S. efforts that was not present during the occupation of Iraq. These diverging strategies ultimately caused two nation-building efforts to chart different courses, but lessons learned in both post-WWII Germany and Japan and post-invasion Iraq now serve as benchmarks of improvement for future U.S. endeavors in nation-building.

Before World War II had officially ended, the United States government had already been hard at work on three stages of preparation that were identical for German and Japan. This period consisted of “the first stage, 1942-43, a time of research and preliminary position papers, the general framework for a new world order and basic principles for the treatment of defeated enemy countries,” “the second period of more advanced work,” and “the third stage of planning [when] political solutions of the Japan specialists had gained wide acceptance.” This punctilious approach was designed in order to create an environment where experts on both host nations would draw upon knowledge of their cultures meant to be incorporated into the framework set up by the postwar governments. In the specific case of Germany, the U.S.-led allied powers “pursued nation-building in Germany by demobilizing the German military, holding war crimes tribunals, helping construct democratic institutions, and providing substantial humanitarian and economic assistance,” and the democratization effort was made easier due to consideration by American experts that Germans of the Weimar Republic had a basic understanding of democratic systems of government. The effort by American planners to create democratic nations that would resemble American structures was expert-driven and required a commitment in time and resources by U.S. military governors in order to keep economic and civil operations stable. Iraq would begin with similar goals of democratization, with Andrew J. Bacevich summarizing the American invasion of Iraq “as the initial gambit of an effort to transform the entire region through the use of superior military power, [and] it not only made sense but also held out the prospect of finally resolving the incongruities bedeviling U.S. policy.” While Iraq had the same general end goals of the postwar occupations of Germany and Japan, the results could not have been more different in Iraq due to inadequate preparation on the part of the U.S. that had been so heavily relied upon in Germany and Japan.

Operation Iraqi Freedom started in 2003 with the primary goal of unseating Iraq’s dictator, Saddam Hussein, in an attempt to create a democratic Iraq that would serve as a benchmark for other countries in the region and encourage them to follow suit. American interests in Iraq were nearly indistinct from the interest in creating stable nations of Germany and Japan, yet Germany and Japan are currently stable democracies and two of the world’s foremost economic powers while Iraq remains mired in intense regional conflict with a weak central government. In the post-9/11 world, there was certainly a desire to see the unpredictability of Saddam Hussein and his threats of possessing WMDs neutralized as quickly as possible. As the arguments of “no blood for oil” also arose in the lead-up to Operation Iraqi Freedom, economist Gary S. Becker dismisses this claim with the fact that “the U.S. would be better off if it encouraged Iraq to export more, not less, oil because that would lower oil prices.” In short, if the U.S. wanted oil from Iraq, war would be incredibly destructive to this objective. However, the Bush administration’s handling of the subsequent occupation of Iraq, according to Michael E. O’Hanlon, “surely includes the administration’s desire to portray the Iraq war as a relatively easy undertaking in order to assure domestic and international support, the administration’s disdain for nation-building, and the Pentagon leadership’s unrealistic hope that Ahmed Chalabi and the rather small and weak Iraqi National Congress might somehow assume control of the country after Saddam fell.” Juxtaposed to the time and resource commitment and intense knowledge of host nations by the American military governments present in Germany and Japan, the effort to nation-build in Iraq was negatively impacted by a less precise and incredibly blunt military intervention that dissolved the current structure without a suitable replacement. The failure of the Bush administration to enact a fully developed strategy only exacerbated the potential for chaos in a host nation O’Hanlon concludes as “still plagued by the continued presence of thousands of Baathists from Saddam’s various elite security forces who had melted into the population rather than fight hard against the invading coalition.” Germany and Japan had robust military governments that sought to create stability before turning power over to the host nation, but their homogenous cultural makeup was another major benefit that the Bush administration did not possess and failed to explore during the occupation of Iraq.

Economic and governmental factors played a large role in the bifurcated end results of post-WWII Germany and Japan and Iraq. U.S. proconsuls’ awareness of the need for a stable governing structure in the former cases and the intelligence gap in the latter case was paramount in determining the differences in end result. In post-WWII Germany, “the occupying powers continued to allow the German central bank to operate, but they, rather than the Germans, exercised control over it,” and “in the U.S. sector, General Clay devoted substantial effort and resources to restarting German factories and mines.” The American nation-building effort had taken great care in ensuring an economically stable system would be in place once occupation of Germany came to an end. This was undoubtedly due in part to the fact that economic blight had crippled Germany in the aftermath of World War I and made the people of Germany susceptible to authoritarianism. American proconsuls were right to address this as a primary component of their nation-building efforts as a means of preventing another politically gifted figure from demagogically exploiting the postwar disarray to promote their own ends in the way Adolf Hitler did during the Weimar period. For this reason alone, economic stability was a driving force for American planners during the reconstruction of Germany. Governance in Germany was also tempered, and American generals were cautious to introduce immediate German rule because of concerns that “a civilian would be lost that quickly after the close of hostilities.” American military governors had a command structure in place, and turning control over to the host nation too soon had the potential of resulting in a breakdown of the fledgling democratic system the U.S. was trying to build if pressured too soon. The invasion of Iraq proved to be a nearly polar opposite approach to the one taken in postwar Germany.

After the toppling of Saddam Hussein and the presence of U.S. troops in Baghdad, the politics surrounding economic structures in Iraq immediately came to the fore. Unlike in Germany, socio-economic development was undermined due to a lack of American knowledge of the major economic resource of Iraq—oil—as Anthony H. Cordesman of CSIS points out:

Iraq’s oil wealth has not been used to create the economic conditions for unity, and is a critical underlying problem in trying to heal its sectarian and ethnic divisions. The [Iraqi Prime Minister] Maliki regime strongly favored itself and Arab Shi’ites over Arab Sunnis, and wavered between efforts to bribe the Kurds and force them to put all petroleum development under central government control.

The failure to understand cultural ties to economic resources in Iraq meant that the United States was already at a disadvantage. Unlike in Germany, American forces had no reliable source to turn over economic control to in Iraq, and the lack of cultural ties to Iraqi economic resources almost ensured sectarian conflict would arise in the absence of the American military. The governing system of Iraq did not fare much better due to the lack of democratic foundation in the country. The nation-building effort in Iraq had the potential to see the new Iraqi government accommodate the multiple sects of its society by “endowing those institutions with popular legitimacy and widespread participation, not merely shifting power and access from one group to another.” Compounded by the insufficient amount of time spent integrating the civilian population into a democratic framework after the military intervention, murky American understanding of the multiple identities of Iraqi society did little to help an increasingly unstable environment.

A clear example of such murky understanding of the Iraqi political structure came from the slash-and-burn approach coalition forces took in the form of de-Ba’athification, or the dismantling of the Ba’ath Party in Iraq that espoused the principles of socialism and Arab nationalism under Saddam Hussein’s authoritarian regime. Any restructuring of the Iraqi political environment would require some degree of de-Ba’athification, but the American approach saw an abrupt shift for a nation that was not united under one national identity in the way the Germans or Japanese were and had deep-seated sectarian struggles. The goal of de-Ba’athification was, according to the Coalition Provisional Authority Order 1, “eliminating the party’s structures and removing its leadership from positions of authority and responsibility in Iraqi society” in order to ensure “representative government in Iraq is not threatened by Ba`athist elements returning to power and that those in positions of authority in the future are acceptable to the people of Iraq.” In doing so, the U.S. comprehensively rebuilt the Iraqi government on a foundation rooted in—among other things—sectarian struggles that would boil over under the Premiership of Nouri al-Maliki, a Shiite Muslim. As Prime Minister of Iraq, al-Maliki set the stage for the current volatility in the region due to what Council on Foreign Relations fellow Max Boot deemed the “victimisation of Sunnis [and] made them receptive to Isis, which was being reborn in the chaos of Syria.” Swaths of Iraqi Sunnis who were suddenly found out of the job as a result of de-Ba’athification were targeted by mass arrests and suppression tactics under al-Maliki that made them feel isolated and under attack. In 2011, AEI scholar Frederick W. Kagan and Institute for the Study of War President Kimberly Kagan wrote that “Maliki is unwinding the multi-ethnic, cross-sectarian Iraqi political settlement” in part due to his exploitation of the effects of de-Ba’athification. Such a comprehensive reorganization of the host nation’s government with no apparent sensitivity to centuries-long sectarian struggles was a major contributor to the failure to achieve political stability in Iraq.

While Germany and Japan had fairly simple ethnic and cultural breakdowns largely due to a sense of national identity, Iraq was unique in this case due to the fact that “oil, ethnicity, religion, tribes, militias, the insurgency, the Sunni Arab boycott of January 2005 elections, and old-fashioned power struggles combined for volatile post-Saddam politics” that had not been accounted for in Iraq. These cultural intricacies led to complications that were less contentious in the examples of Germany and Japan, and the lack of anticipation on the part of the U.S. for these factors made for a messy reorganization of post-intervention Iraq. In his reflections on the Iraq War, Robert Kaplan surmises that “better generalship and logical command chains would likely have improved the security situation, leading to less financial cost, less loss of human life, less opportunity for Iranian meddling, and thus a better geopolitical outcome.” The U.S. benefitted from a stringent chain of command and more homogenous host country in the case of Germany and Japan, but the inadequate anticipation for the dynamics of Iraqi culture and elite structure threaten to put the entire undertaking in severe jeopardy. There was no clear evidence that Bush administration officials were prepared to grapple with the competing sectarian interests present in Iraq that were absent from the nation-building effort in postwar Germany and Japan, and herein lies the issue. The central key to success for any nation-building effort is that the host nation is capable of creating a unified government, and Professor James M. Quirk appropriately observes that “for Iraq, that included Shiites confident that Saddam Hussein and the Ba’ath Party would not return to repress them, minority Sunnis that they would not be repressed by the rise of Shiites to power, and Kurds that much of their autonomy (and oil assets) would be preserved.” Being attentive to this dynamic was crucial at the time of the invasion, and not having a strategy in place to deal with the intricacies of Iraqi culture ultimately led to intense sectarian violence.

The future of Iraq is one that now seems uncertain with the rise of ISIS and internecine conflict between different regions of the country that are at odds due to their competing identities. While it is uncertain what, if anything, the U.S. can do to turn the deteriorating situation in Iraq around, a suggestion by Sen. Marco Rubio (R-FL)—a member of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and Senate Select Committee on Intelligence—takes sectarian relations into account in order to “negotiate a power-sharing deal that will give predominantly Sunni provinces, such as Anbar and Nineveh, assurances that their rights will be respected by Baghdad.” Though this is imperfect as a sole solution due to the fact that sectarian divides are not the singular cause of Iraq’s current political instability, Sen. Rubio offers a perspective that incorporates sectarian conflict in a way not seen in the planning for post-invasion Iraq. Future U.S. sensitivity to the cultural identities and awareness of the power dynamics at play are paramount to establishing governmental structures that will in turn function constructively with respect to Iraqi culture. As with Germany and Japan, the U.S. withdrawal of forces in 2011 does not mean an end to advising, but the Iraqis are now—whether they were ready to in 2005 or not—beginning to govern themselves. For the future of Iraq to regain stability despite the instability in the region, the current U.S. nation-building effort should be conscious of the fact that “early difficulties, and even early failures, will not indicate long-term disorder as long as the key representative interests remain committed to this kind of politicking instead of retreating to coups, secession or open advocacy of violence.” The best course of action for U.S. planners in Iraq is to be cognizant of competing sectarian interests while allowing these differences to be dealt with politically as opposed to violently and facilitate discussion where need be.

The post-WWII German and Japanese nation-building efforts succeeded because of a logical chain of command and significant time and resource investments that sought to steadily revert power back to the host countries; Iraq’s failures resulted from a loosely-defined command structure after regime change and a lack of understanding by U.S. planners of the rudiments of Iraqi cultural diversity in a way not seen in the German or Japanese examples. Though the results of poor foundational handling after regime change are seen in modern-day Iraq, there are still lessons that can be gleaned from previous nation-building successes in Germany and Japan. Future U.S. foreign policy—if it is to still be one of championing democratization abroad—would do well to observe the future of Iraq and remember the lack of foundational planning as a benchmark for improvement if future nation-building efforts are to be beneficial to U.S. foreign interests.

Overestimating Refugees’ Economic Impact: An Analysis of the Prevailing Economic Literature on Forced Migration

Contributing Editor William Kakenmaster disproves prevailing myths surrounding refugees’ economic impact.

The UNHCR reported in June 2016 that the number of number of refugees, asylum seekers, and internally displaced persons reached a record high of 65 million individuals worldwide. How will all these individuals impact the economies of the countries in which they find asylum? Do refugees, as some politicians claim, force domestic workers out of the labor market? Do refugees exert a substantially negatively net fiscal impact? This paper attempts to address these questions by analyzing the prevailing economic literature from 1990 until the present on refugees’ and immigration’s economic impact. I argue that, although the estimated economic effects of immigration and refugees vary, their overall impact is negligible. Refugees exert a slightly negative impact on domestic wages if domestic labor is immobile. At the same time, refugees’ net fiscal impact depends more on their tax contribution—which is a function of their labor market integration—than their consumption of publicly funded goods and services.

Overview

Refugee and forced migration issues have dominated recent political debates in Europe and other parts of the world. Those on the political Right claim that refugees threaten European national security, economic prosperity, and cultural traditions; those on the political Left claim that the influx of refugees represents a humanitarian crisis that demands accepting additional refugees. Perhaps the Economist’s attempt to reconcile these two opposing opinions puts it best: “Humanity dictates that the rich world admit refugees, irrespective of the economic impact. But the economics of the influx still matters.” Setting aside that international law does require states to provide refugees with asylum, this paper attempts to address the two most salient economic questions regarding refugees’ arrival in Europe.

First, do refugees displace domestic workers, leading to higher rates of unemployment and lower wages? Second, do refugees exert significant strains on public finances? While perfect data do not exist to answer either of these questions beyond the shadow of a doubt, evidence suggests that, in the short run, granting refugees asylum leads to a negligible overall effect on the labor market and public finance. In the long run, however, refugees positively contribute to the labor market and public finances, the extent of which depends mostly on the success of their integration into the economy.

Refugees and the Labor Market

Economists disagree about the precise nature and extent of immigration’s impact on the wages and unemployment rates in immigrant-receiving countries. On the one hand, some studies suggest that immigration has “essentially no effect on the wages or employment outcomes” of domestic workers. David Card’s famous analysis of the Mariel Boatlift found that refugee immigration had a positive, yet minimal impact on the Miami economy due to the city’s ability to absorb refugees into previously unexploited sectors. On the other hand, George Borjas argues that, because of labor mobility, the impact of immigration on unemployment and wages may be tenuous in regional labor markets, while simultaneously depressing labor market conditions at a national level. Borjas measured skilled and unskilled immigrant labor in terms of educational qualifications and found that a 10 percent increase in the labor force due to immigration resulted in a three to four point decrease in domestic workers’ wages.

However, other studies attempt to find some sort of middle ground, disputing both the argument that immigration has no effect on the labor market and the argument that immigration drastically depresses wages and employment. Gianmarco Ottaviano and Giovanni Peri, for instance, adopt the qualification bands from Borjas’ framework, but they assume that, even within those bands, immigrant and domestic workers are not perfect substitutes. In other words, immigrants with the exact same educational qualifications as domestic workers can function as “imperfect substitutes” because of labor market discrimination. Even if immigrants could do the same job as domestic workers, they don’t practically function as perfect substitutes because, in reality, they may not be hired by employers who consider them less capable because of their race, ethnicity, nationality, language, etc. As a result, Ottaviano and Peri find that immigration has “a small effect on the wages of native workers with no high school degree (between 0.6% and +1.7%) […and] a small positive effect on average native wages (+0.6%).” Moreover, Ottaviano and Peri also note that, given the standard error, this effect is not “significantly different from 0.” The largest impact on the labor market observed was on the wages of previous immigrants, which were found to have “a substantially negative effect (−6.7%).” Thus, even at the theoretical level, the effect of immigration on the labor market has been highly contested.

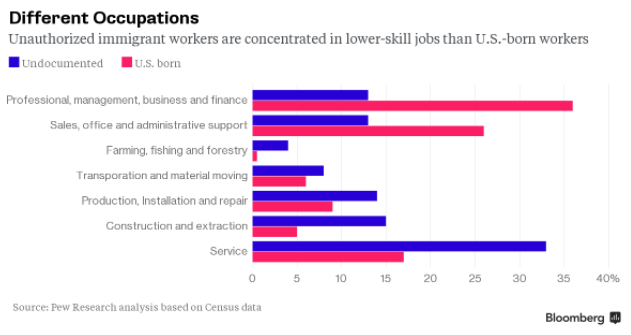

Later, even more tweaks were made to the traditional methodology used to study the economic effects of migration. Stephen Nickell of the University of Oxford and Jumana Saleheen of the Bank of England recently studiedmigration’s impact on average British wages in any given region of the country between 1992 and 2014. Crucially, Nickell and Saleheen measure skill distribution by occupation, a clever methodological tweak considering “that it is often very tricky to accurately compare education qualifications across countries.” In addition, treating skill distribution as a function of occupationhelps to translate the economics of migration directly into the jargon of public discourse, which treats immigrants principally by occupation rather than by educational attainment, such as with the “stereotype of the Polish plumber—used widely as a symbol of cheap labor.” Ultimately, Nickell and Saleheen findthat migration exerts “a statistically significant, small, negative impact on the average occupational wage rates of the regions” studied. The largest effect on wages observed related to semi-skilled and unskilled labor, where a 10% increase in migrant labor resulted in a 2% decline in the average wage. Nickell and Saleheen’s occupational measure of qualification might be said to be more accurate than educational measures such as Borjas’ considering that, oftentimes, educational credentials do not transfer between countries. Therefore, Nickell and Saleheen’s findings suggest that refugees immigrating to Europe may adversely affect the labor market, but not nearly to the extent that some politicians claim.

Moreover—and with specific regard to refugees—the Economist notes that the wage-dampening may “even have positive side-effects” for the domestic labor market. A recent paper by Mette Foged and Giovanni Peri finds that, in Denmark between 1991 and 2008, domestic workers pushed out of low-skilled industries by refugees changed jobs to other, “less manual and more cognitive” labor-intensive sectors. Such jobs included “legislators and senior [government] officials,” “corporate managers,” and even “skilled agricultural and fishery” sectors. By contrast, the proportion of refugees composing manual skilled sectors such as “machine operators,” “drivers,” and “mining laborers” rose substantially, resulting in “positive or null wage effects and positive or null employment effects” for domestic populations over the long run. So, to the extent that refugees substitute for domestic labor—however imperfect that substitution may be—their overall economic impact also depends on the abilities of displaced domestic workers to find employment in other sectors. Additionally, evidence exists from Congolese refugee camps in Rwanda to suggest that one additional refugee receiving cash aid contributes an estimated $205 to $253 to the local economy. Taking the difference between contributions and per-refugee cash aid, refugees yielded a positive individual contribution of between $70 $126 annually. Most of the refugees’ individual contributions resulted from spillovers with the local economy, such as the “purchase [of] goods and services from host-country businesses outside the camps.” If refugees displace workers who move into other sectors of the economy and experience higher wages, then they also positively contribute to the sales of local businesses.

Refugees and Public Finances

Refugees exert a similarly ambiguous impact on public finance as they do on the labor market. In fact, a 2013 OECD report notes that including or excluding non-personal sources of tax revenue, such as corporate income taxes, as well as non-excludable goods like roads, in an analysis of immigrants’ net public fiscal impact “often changes the sign of the impact” itself. Estimates of immigrants’ net fiscal impact thus vary depending on the methodology employed, although the report’s main findings suggest that—however measured—the impact “rarely exceeds [plus or minus] 0.5% of GDP in a given year.” In fact, the OECD observed the highest impact on public finance in Luxembourg and Switzerland, where immigrants positively contributed an estimated 2% of GDP to the public purse. Compared to domestic populations, however, the OECD report found that, on average, immigrants have a lower net fiscal contribution overall.

This is an especially salient concern in the short run, because refugees can potentially exacerbate strains on the public purse, contributing to increases in demand for public services while the supply of those resources remains temporarily fixed. In fact, precisely because of the protections afforded to asylum seekers under international law, “additional public spending for […] housing, food, health, and education, will increase aggregate demand,” therefore making such services more costly to provide, all else equal. However, in many cases, the short-term costs of accommodating asylum seekers are borne by international donors rather than governments. In fact, University of Oxford Professor Emeritus Roger Zetter notes that global programs to accommodate refugees in the short term total 8.4 billion USD globally, but that economists “rarely analyze the economic outcomes of their program[s].” Instead, they “tend to assess the impacts and costs for the host community” as a percentage of GDP regardless of whether or not the government actually pays for the accommodations provided to refugees. Such analyses are frankly misleading because, while aggregate demand for publicly funded goods may increase in the short run, the cost of meeting such a higher demand puts strain on NGOs, the UNHCR, and other international donors, not on governments.