The Truth Behind the “Illegal Alien”: Debunking Anti-Migrant Talking Points

Image credit: U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE)

In the past few weeks, President Donald Trump declared a national emergency at the southern border, attempted to end birthright citizenship, suspended US refugee admissions, shut down the Biden administration’s immigration programs, and ordered for Guantanamo Bay to be prepared to house up to 30,000 migrants. Amongst this barrage of activity undertaken by President Trump, nothing exemplifies the US shift to reject its “melting pot” roots more than the intense influx of raids by US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), paired with his consistent anti-immigrant rhetoric. The recent ICE raids have evidenced racial profiling, with American citizens being detained on the basis of their race or skin color, including indigenous American citizens of tribal nations. ICE has also been granted the authority by President Trump to apprehend migrants in or near schools, churches, and hospitals, prompting pushback from public schools. Sowed by claims of high crime rates from undocumented immigrants and stolen American jobs, the seeds of xenophobia have been planted quite deeply. But is there any factual basis to these anti-immigrant arguments?

The extreme rise in anti-immigrant hate, discrimination, and administrative action necessitates an examination of the truth and facts on the topic. In an assessment of the common arguments against migrants in the US, there is little to no evidence supporting the claims of high crime rates, violence, and job-stealing.

CLAIM: Migrants are criminals, murderers, terrorists, violent, etc.

“Not only is Comrade Kamala allowing illegal aliens to stampede across our border, but then it was announced about a year ago that they’re actually flying them in. Nobody knew that they were secretly flying in hundreds of thousands of people, some of the worst murderers and terrorists you’ve ever seen,” said Trump at a news conference in Los Angeles, California on September 13, 2024.

FACT: Data indicates that immigration, including undocumented populations, is not linked to higher crime rates; in reality, the inverse is true.

Studies have shown that immigration is not linked to higher crime rates. In fact, communities with greater immigrant population concentrations have been observed to have lower crime rates and increased levels of social connection and economic opportunity, which are factors indicative of neighborhood safety.

Additionally, when it comes to claims of terrorism, a 2019 CATO Institute study examined terrorist attacks from 1975 to 2017 and found no association between immigration and terrorism. The study assessed terrorism’s relationship to immigration status, comparing native-born terrorism to foreign-born and undocumented migrants, and found that, in the 43-year period analyzed, there were 192 foreign‐born terrorists and 788 native-born terrorists who planned, attempted, or carried out attacks on U.S. soil. The vast majority of attacks that were planned, attempted or carried out were made by native-born terrorists. Additionally, the chance of a citizen being killed in a terrorist attack by a refugee on U.S. soil is about 1 in 3.86 billion per year, and the chance of being murdered by an attack committed by an undocumented immigrant was found to be zero.

Cases such as the tragic murder of Laken Riley have been wielded as examples and proof of this migrant-criminal generalization, despite their statistically unlikely nature. Native-born US citizens have been found to have significantly and consistently higher rates of violent crime in comparison to undocumented migrants, although these instances receive far less media attention. The case of Laken Riley in particular became a major campaign talking point for President Trump, who signed into law the Laken Riley Act in her honor. Ultimately leading many to overestimate the crime risks of migrants, specific cases like this have been utilized to continue the dissemination of the dangerous migrant narrative.

CLAIM: Migrants steal American jobs and hurt the US economy.

“Virtually 100% of the net job creation in the last year has gone to migrants. You know that? Most of the job creation has gone to migrants. In fact, I’ve heard that substantially more than — beyond, actually beyond that number 100%. It’s a much higher number than that, but the government has not caught up with that yet,” said Trump in August of 2024.

FACT: Immigration helps boost the economy, and is not linked to higher American unemployment.

The Congressional Budget Office reported in 2024 that immigration contributes significantly to economic growth, rather than stunting it. Economists believe that post-pandemic, the surge in immigration led to growth in the economy without contributing to price inflation.

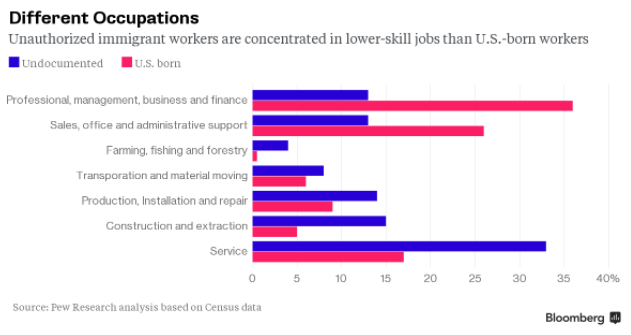

Furthermore, concerns about migrants stealing jobs from Americans have also been debunked. The rate of unemployment for US-born workers averaged around 3.6% in 2023: the lowest rate on record. The claim that more immigrants displace US-born workers is simply not factual, otherwise the unemployment rate would be significantly higher. The truth is that US-born workers have very low interest in labor-intensive and commonly agricultural jobs, which are then filled by migrants.

Government data indicates that immigrant labor actually provides promotional opportunities for US-born workers, and that a mass-deportation event would cause costs of living to skyrocket. This is because immigrants tend to take jobs that are complementary to native-born workers, not acting as substitutes to them, but as supplements. Additionally, immigrants contribute not only to the labor supply, but to labor demand as well due to their consumption of goods and services. This is furthered by the entrepreneurial tendencies of many high-skilled immigrants; immigrants have been found to start businesses at higher rates than native-born workers, generating jobs and long-term economic growth.

CLAIM: Migrants should just go back to their own country.

“Why don’t they go back and help fix the totally broken and crime infested places from which they came,” tweeted Trump in 2019, targeting progressive Democrat congresswomen who had been outspoken against his immigration stance.

FACT: According to a study on those migrating to the US from Latin America and the Caribbean, nearly 73% have been victimized by violent crime in their home countries, many of which have been destabilized throughout history by US interventions.

The largest population of migrants in the US is from Mexico, making up around 23% of the country’s total immigrant population. In 2022, a UN International Organization for Migration survey found that 90% of Mexican migrants fled due to violence, extortion, or organized crime.

Similarly, undocumented immigration from the Northern Triangle (El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras) has been increasing steadily over the past 30 years. Looking at the US involvement in these countries, all three have been destabilized by past US intervention.

During El Salvador’s 12 year long civil war from 1979 to 1992, the US government backed the repressive regime that dispatched paramilitary death squads against civilians. Post-war, El Salvador saw an explosion of gang violence across the country. Guatemala has been plagued by national instability for decades, which was largely exacerbated by a 1954 CIA-backed coup that triggered an armed insurgency. Guatemala has since faced decades of human rights abuses committed by its leaders. The 2009 Honduras coup was supported by US DoD officials, and led to an age of violence and instability in the country that's effects are still felt today. Post-coup, Honduras has faced extreme poverty, economic inequality, and gang violence.

Additionally, studies have examined the distinct correlation between US firearm manufacturing and the rates of gun violence in Latin America and the Caribbean. The US Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives indicates that a large sum of guns recovered from crimes in El Salvador, Honduras, and Mexico were manufactured in the US. The US remains one of the main legal firearm exporters to Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador, and the US Government Accountability Office reported that these legal exports are often diverted to criminal networks.

Global migration has increased overall over the past few decades, hitting a record high in 2023. As of May 2024, over 120 million people have been forcibly displaced due to human rights violations, persecution, conflict and violence around the world, including 6.4 million asylum seekers.

CLAIM: They should just come into the country legally.

“The current administration terminated every single one of those great Trump policies that I put in place to seal the border. I wanted a sealed border. Again, come in but come in legally,” said Trump in his speech at the Republican National Convention in July of 2024.

FACT: It’s not that migrants do not want to enter legally, but rather structural, institutional, and financial obstacles impede them from doing so.

Many migrants do want to come into the US legally. The process however, is extremely time-consuming and difficult to navigate. In the years following the outbreak of COVID-19 there has been a massive backlog in cases, amounting to 2 million pending cases in 2023— more than triple the amount from 2017. Partly due to understaffed immigration courts, the backlog means years of waiting for a case to be heard. Beyond shortages in immigration judges and staff, the DOJ’s Executive Office for Immigration Review has been found to have “longstanding workforce management challenges,” and “did not have a strategic workforce plan to address them,” according to the US Government Accountability Office.

Additionally, immigrants and asylum seekers are five times more likely to win their case if they have a lawyer. Unfortunately, publicly-funded lawyers are not a right for migrants, and even if they were , there is a massive shortage in immigration lawyers to begin with, and they are often far too costly to obtain. To make matters worse, many migrants don’t speak English, and ICE provides little guidance on how to go about legal processes, and certainly not any translated versions of instructions or resources.

THE BOTTOM LINE:

As Trump continues his flurry of anti-immigrant actions, it’s essential to remain vigilant to the facts and truth. We must work to see these baseless claims as what they truly are: hateful rhetoric, not factual arguments. Diversity in the US should be celebrated, not abhorred. Dehumanizing language should have no place in the US government, especially not in our highest office. Maintaining a high integrity of indiscrimination and empathy for one another is more necessary now than ever, especially in wake of Trump’s anti-DEI initiatives.

All of these actions are justified by Trump with claims of high levels of violence and crime committed by undocumented immigrants, often paired with extremely degrading language of animalistic and impure nature. The claims by Trump of migrants being “animals”, “not people”, and “poisoning the blood of our country” strikingly resemble the verbal dehumanization that precedes massive cultural violence and genocide. In his book Mein Kampf, Adolf Hitler used the phrase “blood poisoning” as a way to criticize the mixing of races, and during the Rwandan Genocide Tutsis were commonly referred to as “cockroaches”. This sort of dehumanization is designated as the fourth of the ten stages of genocide.

With the first flights full of deported migrants landing in Guantanamo Bay this past Tuesday, our full attention must be on the treatment of migrants, legality, and ethics of this detainment. Guantanamo Bay has repeatedly been subject to strong criticism by human rights groups for violating basic human rights, holding detainees without charges or trials, and violating the US Constitution; the implications of holding deported migrants at the facility are quite alarming, with high potential for human rights abuses obscured from the public eye.

The Trump Administration’s Oncoming Attack on Birthright Citizenship: What Does It Mean to Be an American?

Via Flickr

American birthright citizenship, and the associated rights and liberties, is core to the American experiment. The idea that someone born in the fifty states, regardless of their race, gender, status, or parents’ country of origin, is entitled to all of the freedoms, protections, and civic responsibilities that the United States has to offer, is an incredibly compelling one. American citizenship is intrinsic and inalienable. It has given us some of the nation’s best and brightest and created a distinct national identity; we can recognize our distinct ethnic, religious, or regional differences while living in the same communities, voting together, catching a football game, and so on. It unifies us – we are all “one America.” It is what allows American communities to become cohesive and truly great; removal and separation breaks down the communities that make up our nation. It is this integral, compelling core value that is being challenged by recent executive orders by the Trump administration.

Mere hours after being inaugurated again, President Donald Trump signed an executive order “Protecting the Meaning and Value of American Citizenship.” In doing so, the Trump administration seeks to “protect” American citizenship by redefining birthright citizenship to require both parents of a child to, at minimum, be legal residents of the US (green card holders) or full citizens. Prior to this, any child born on US soil was granted birthright citizenship, regardless of their parents’ legal status or nationality. This principle was codified in the 14th Amendment, which was designed to overturn the court precedent established in Dred Scott v Sanford, the landmark 1856 Supreme Court case that denied African-American slaves American citizenship despite being born on American soil. It was further solidified in another SCOTUS case, United States v Wong Kim Ark, in which a Chinese-American born in San Francisco had been denied citizenship on the basis that his parents were Chinese nationals during the time of the Chinese Exclusion Act, even though his parents were considered permanent residents of the United States. Ultimately, in the case Wong Kim Ark was found to be a citizen, therefore establishing the precedent that the parents’ origin is irrelevant to the citizenship status of their child. Birthright citizenship applies in almost all cases, with children of foreign diplomats being the only exception, as they’re not “subject to the jurisdiction” of the United States. The question is, how does this executive order overturn years of legal convention?

It is that exact phrasing in the 14th Amendment, “subject to the jurisdiction thereof” (meaning the jurisdiction of the United States) that the Trump administration has used to justify the executive order. In essence, the executive order asserts that a child born to parents that are not in the United States legally or are in the United States temporarily (on a visiting or student visa) is therefore not subject to the jurisdiction of the United States, but rather the parent’s country of origin. In other words, the administration has exploited the vagueness of the terminology to say that the US has no legal responsibility to someone whose parents do not hold permanent residence in the US. Executive orders, from a legal standpoint, are used to direct how the executive branch should enforce legal policy; often, they are used to enact policy that would otherwise be legislatively difficult, but it is still possible to legally challenge or prevent an executive order through the legislative and judicial branches. For the time being, a federal district court judge has blocked the order temporarily on the grounds that it is built off a bad-faith constitutional interpretation, calling it “blatantly unconstitutional.” But, the directive still holds political weight; it makes good on Trump’s political promises, yes, but it also establishes a more essentialist view on what it takes to be an American, especially in the context of the country’s changing demographics and rising rates of global migration. Moreover, it is an order that, while likely to be overturned, still inflicts fear in both his political opponents and any prospective migrants.

Where do we go from here? Should the case go to the Supreme Court, there is a good chance that even the Trump-appointed justices break from the administration. Justice Amy Coney Barrett has been shown to break rank in favor of logical and clear constitutional rulings, highly valuing her own conservative principles and not wanting to serve as a mere pawn to the Republican agenda. Chief Justice John Roberts places high value on judicial precedent; this is evident in his concurring opinion in Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Organization, in which he emphasizes judicial restraint and stare decisis. Justice Neil Gorsuch has also occasionally taken more diverse ideological stances, authoring the majority opinions in Bostock v Clayton County and McGirt v Oklahoma, opposing discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and in support of the sovereignty of Native American lands. Something with this clear of a judicial precedent is unlikely to be overturned easily, but it is still a possibility; in recent years, the court has shown a willingness to overturn long-held precedent, especially given the recent decisions overturning Roe v Wade and Chevron v NRDC. More than that, however, this executive order has opened the political and ideological floodgates. The country is facing an intense, vehement reckoning over immigration, from the looming crackdown on irregular migration to the political battles over H-1B (work visa) recipients. Amid these political battles, we again ask, what is the meaning and value of American citizenship? Who deserves to be a citizen? This executive order may well be a step toward a narrower, more exclusive definition of what an American citizen is.

Meloni's English Ban: An analysis into Italian Prime Minister, Giorgia Meloni's proposed legislation to fine foreign languages

Executive Editor, Caroline Hubbard, analyzes the implications of a proposed foreign language ban within Italy’s governmental institutions.

In March of 2023 the party of Italian Prime Minister, Girogia Meloni, proposed introducing a new piece of legislation that would seek to address the growing issue of the dominance of the English language across Italy and the issue of Anglomania (the obsession with English customs), all in hopes of countering growing fears over the loss of Italian language and culture. The legislation proposes fines of up to 100,000 euros on public and private entities using foreign vocabulary in their official communications and requiring all company job titles to be spelled out in the official local language.

Meloni’s new legislation seeks to address what her party sees as key cultural issues affecting Italian society. On the surface level, the legislation is an attack against EU integrationist policy and an attempt to promote Italian cultural power. Although this legislation may seem both amusing and bizarre from an outside lens, its implications, both politically and socially, could be tremendous. Only through placing this language ban in the context of Meloni’s immigration policies can we understand the greater intent; Meloni’s legislation is a direct threat towards Italy’s growing immigrant population, who often lack Italian language skills and can often only hope to communicate with Italian government officials in a shared second language, English.

Italy’s changing image

At its core, Meloni’s legislation reveals a growing fear and frustration brought on by fear over losing Italian cultural identity and frustration with the English language's dominance across all sectors.

Like their fellow EU neighbors, Italy has struggled in recent decades to come to terms with its new multi-cultural identity, brought on by increases in immigration and participation in international communities and systems. Italy’s recent immigrant population is largely dominated by migrants and refugees from Eastern Europe and Northern Africa. Non-white Italians report a level of discrimination and isolation despite spending decades in the country. Michelle Ngonmo, a Black Italian fashion designer stated that “there is a real struggle between the people-of-color Italians and [white] Italian society. Asian Italians, Black Italians are really struggling to be accepted as Italians.”

The changing demographics of Italy reflect a country grappling with its newfound cultural identity. While many have embraced the tide of immigration as both a benefit and reality of globalization, Meloni’s political party has deliberately ignited anti-immigrant spirit.

The Brother’s of Italy

Meloni leads the Brother’s of Italy party (Fratelli d'Italia), a nationalist and conservative far-right party that has its roots in neofascism. After co-founding the party in 2012, she led the party through a series of political victories, eventually emerging as the preeminent far-right party in Italy.

Similar to other far-right parties across the continent, such as the National Rally in France or the UKIP party of the UK, the Brother’s of Italy embodies many populist values and policies, including anti-globalization efforts, xenophobia, and an emphasis on national unity and heritage. However, the Brother’s of Italy has deeper roots in historical notions of facism, tracing back to the first postwar Italian neo fascist party known as the Italian Social Movement (Movimento Sociale Italiano or MSI, which existed from 1946 to 1995) as well as the Salò Republic which was known for its Nazi-origins. The predecessors behind the Brother’s of Italy party reveal a political party that is steeped in decades of fascist theory. Meloni was a member of the MSI youth party in the early 90s that became known for its far-right magazine, Fare Fronte and adoption of French far-right ideals. Political upheaval and turmoil caused by political corruption scandals across Italian politics led to the end of the MSI in 1995, but elements of the party continued.

Meloni’s rise to power

The well known youth party transformed into Azione Giovani (Young Action) which was at this point associated with the Alleanza Nazionale (National Alliance party or AN) the successor of the MSI. Meloni held a position on the youth leadership committee which led her into politics. At age 19 she was filmed praising fascist dictator, Benito Mussolini, as an example of strong leadership in Italian politics.

She was elected as Councilor for the Province of Rome in 1998 which she held for four years. She continued to develop her political career by becoming the youngest Vice President to the Chamber of Deputies in 2006. Her experience in far-right youth organizations led her to become the Minister of Youth under the fourth Berlusconi government. Then in 2012, she founded the Brother’s of Italy party alongside fellow politicians, Ignazio La Russa and Guido Crosetto. Throughout Italy’s rocky political climate of the 90s and 2000s, Meloni positioned herself as a politician loyal to far-right causes, but also able to adapt to contemporary political climates.

In a speech from 2021, Meloni identified her far-right values, saying, “Yes to the natural family, no to the LGBT lobby, yes to sexual identity, no to gender ideology... no to Islamist violence, yes to secure borders, no to mass migration... no to big international finance... no to the bureaucrats of Brussels!”

Meloni has routinely denied that her party has any connection with fascism; she has denounced Mussolini and his reign of fascist terror in speeches, citing Mussolini’s racial laws as one of the darkest points in Italian history. However, her latest proposed legislation to restrict the use of English and promote Italian reveals Meloni’s nationalistic approach to uniting the Italian people as well as a denial of Italy’s multiculturalism.

Contemporary fascism

Meloni’s political career has flirted with fascism from the beginning. We can witness it in her blatant statements of support for Mussolini as a young youth leader, but also in the inherent nature of her political positioning in parties rooted in fascism. Meloni’s critics are quick to call her a fascist or “fascist-adjacent” for her political remarks, her friendship with Hungary’s authoritarian leader, Viktor Orbán, and her ultraconservative values. Although these points are all valid and true, they do not actually threaten Meloni’s political standing or reputation, but instead allow her to counter the remarks and paint her opponents and critics as irrational left-wing radicals. Meloni simply has to deny her associations with fascism, something she has done on numerous occasions, such as during her pro-EU speech following her inauguration in which she also spoke out against Italy’s fascist past. International attention on Meloni’s fascist roots has shifted attention away from the real danger of her ultra-conservative politics, which intend to restore traditional Italian values and relies on tactics of alienation and discrimination.

Anglomania

Meloni has stated that her proposed legislation is an attempt to protect Italian national identity, which she sees as weakened by the dominance of English as the international language of business and politics. It is true that English has become the lingua franca of the world, dominating arenas such as international institutions, cultural interests, and educational institutions. However the bill does not only call for the ban of English but words from all foreign languages in businesses. The legislation also called for university classes that are “not specifically aimed at teaching a foreign language” should only be taught in Italian, thus preventing the likelihood of English-speaking classes taking precedence. Yet Meloni’s legislation makes it clear that her desire to protect Italy’s cultural heritage is rooted in populist and far-right xenophobia.

Foreign residents make up around 9% of Italy's population. Italy is also home to the third largest migrant population in Europe, following the migrant crisis of the past decade. The change in population has brought varying forms of anti-immigration sentiment. Meloni has been at the forefront of the movement during her political campaign and time in office. Her first act of anti-immigration legislation in November of 2022 attempted to prevent adult male asylum seekers from entering the country. Italy’s interior minister, Matteo Piantedosi, claimed that the reason behind this policy was that these people are “residual cargo,” unworthy of being rescued and Meloni referred to recent immigrants to Italy as “ethnic substitution,” implying that ethnic Italians are in danger simply from their population’s change in ethnic and racial diversity.

Meloni’s proposed language ban must be understood in the context of her prior legislation and political viewpoints; this is more than a critique of the dominance of the English language and the promotion of Italian culture. Meloni’s ban is a threat to all immigrants and foreign-born Italians as a sign of Italy’s growing preference for an homogenous ethnic population and anti-immigration policies.

A broken immigration system: the extension of the Title 42 immigration policy leaves many Cuban asylum seekers in crisis

Staff Writer, Candace Graupera, explores the impact of the extension of Title 42 on specifically Cuban asylum seekers and the perpetuation of the United States’ broken immigration system.

After five years of saving money, Patri, from Havana, Cuba, was ready to make the trek to the United States. Cuba’s economic crisis has become so dire in the past few years, due to COVID-19. The cost of living has been steadily rising and there has been an increase in food shortages. In 2022, 2% of Cuba’s population left for the U.S. and Patri hoped to be one of them. She saved up the equivalent of 8,000 dollars. However, this was rendered impossible by the Supreme Court’s decision that extended Title 42’s immigration policy. Now if you are seeking asylum, as Patri is, from four countries, Cuba, Venezuela, Nicaragua, and Haiti, you have to apply for a parole process. The process allows only 30,000 migrants to enter the U.S. per month and the qualifications are steep. You need to have a valid passport, pass a background check, afford the airfare, and have a sponsor with legal status who is already inside the U.S. that can help to support you financially. If you do not have a sponsor, as Patri doesn’t, you will be turned away at the border and forced to remain in Mexico for the time being. For many, this can be a death sentence, left vulnerable to theft, homelessness, and kidnapping for ransom. Despite these risks, many migrants make the trek anyway because they simply have no other alternative. The extension of the harmful Title 42 immigration policy by the Supreme Court and the Biden Administration leaves many Cuban asylum seekers in a crisis due to unreasonable restrictions. In response, the Biden Administration has put forth future policy changes to counteract the extension of Title 42 that will hopefully accomplish its goal of fixing the broken immigration system.

What is Title 42?

Title 42 is a U.S. law used in issues such as civil rights, public health, social welfare, and more. The government can use it to take emergency actions to keep contagious diseases out of the country. It was first used in 1929 during a meningitis outbreak to keep Chinese and Filipino ships from entering the U.S. and spreading the disease. The law was only enacted again in 2020 by then-president, Donald Trump, due to the global COVID-19 outbreak. However, Trump also used this law and its implications to turn away migrants from the border more quickly without having to consider their cases for asylum. Since this law has been put into effect in 2020, 2 million people have been barred from entering the U.S.

The Trump Administration’s impact on immigration policy

Donald Trump’s campaign and presidency are defined largely by his harsh views and policies on immigration and enforcement. There are 100 million displaced refugees in the world today, a number that only grew worse during Trump’s presidency. He reduced legal immigration into the United States by 49%. From 2016-2019, there was an increase in denials for military naturalizations by 54%. During his presidency, 5,460 children were separated from their families at the U.S.-Mexico Border. In 2017, he announced that he would dismantle DACA, Deferred Actions for Childhood Arrivals, which provides relief from deportation and work authorization for immigrants brought to America as children. He also tried to terminate TPS, Temporary Protected Status, a program that grants legal status – including work authorization and protection from deportation – to people from designated countries facing ongoing armed conflict, environmental disaster, or other extraordinary conditions preventing their safe return. Hate crimes against Latinos and Hispanics rose by 21% in 2018. By increasing his anti-immigrant rhetoric, he made the issue of immigration one of the top priorities in the 2020 election.

The Biden Campaign’s immigration policy promises

Since immigration played a powerful role in the 2020 election, the Biden campaign put out extensive information on how he was going to help fix the immigration crisis if he was elected to office. He starts by evoking emotion in his plan by saying, “It is a moral failing and a national shame when a father and his baby daughter drown seeking our shores. When children are locked away in overcrowded detention centers and the government seeks to keep them there indefinitely.” He ultimately, flat-out states, “Trump has waged an unrelenting assault on our values and our history as a nation of immigrants. It’s wrong, and it stops when Joe Biden is elected president.”

Biden states overall goals for immigration policy, such as modernizing the immigration system and welcoming immigrants into the community. However, since this election was about defeating Trump and reversing his policies, Biden created promises for his first 100 days in office. These include, “Immediately reverse the Trump Administration’s cruel and senseless policies that separate parents from their children at our border” and “End Trump’s detrimental asylum policies.” He wants to end the separation of families at the border by ending the prosecution of parents for minor violations since these are mostly used as scare or intimidation tactics. He said that he wants to restore asylum laws so they can actively protect people fleeing persecution. The Trump Administration put restrictions on access to asylum for anyone traveling through Mexico or Guatemala and those fleeing from gang or domestic violence.

The economic crisis in Cuba

Why are there record numbers of migrants leaving Cuba for the United States? The number of migrants (200,000 in 2022) reflects percentages that haven’t been seen since the 1990s, and it's because Cuba is facing its worst socio-economic crisis since the collapse of the Soviet Union. There are daily shortages of food and medicine. There are regular power outages and last year during a protest against the government, the internet was switched off. Shortages of resources have culminated since 1962 when the U.S. trade embargo was imposed. To survive, Cuba has become reliant on earnings from international tourism and Cuban nationals working abroad. Due to COVID-19, the island was mostly closed off to foreign tourists and reduced visitor numbers by 75% in 2020. When Trump was elected in 2016, he reinstated longstanding travel and business restrictions between Cuba and the U.S., further closing them off from U.S. resources. He also reinstated Cuba to the list of state sponsors of terrorism, which obstructed the country’s access to international finance.

In the last few years, resistance to the government has risen, partly due to social media and the internet. There are increased demands for political and economic change and for government officials to be held accountable. In 2021, there were massive Cuban protests that were fuelled by COVID restrictions and food and medicine shortages. Due to limited resources provided by the government, many were forced to turn to the black market. Many preferred to work for and sell on the black market because they usually made more money than a salary at a typical job to cover basic needs. The Cuban's ability to be resourceful and stretch themselves thin is running out and unless there is significant economic change, many more are bound to follow the 2% of the population that have already left in 2022.

Impact of the continuation of Title 42 on Cuba and asylum seekers

The continuation of Title 42 could create an asylum crisis for many Cubans. An official from the Washington Office on Latin America, a human-rights nonprofit, estimates that people like Patri, without a sponsor, have no chance of crossing the border anytime soon. While she and many others wait in Mexico for their case to be heard, they would be risking dangerous conditions such as homelessness and kidnapping for ransom. Oftentimes, appointments for Title 42 expectations get booked as soon as they become available and people have to wait weeks to have their cases heard.

Since there are so many restrictions, many Cubans are turning to more creative ways to migrate to the U.S. In 1994 there was a Cuban rafter crisis or balseros crisis where 35,000 Cubans migrated to the U.S. on makeshift rafts. They spent all their money on the materials to make a raft and row across the Gulf of Mexico to Miami, Cuba. After five weeks of riots, Fidel Castro announced that anyone who wanted to leave Cuba was welcome to do it without hindrance. However, President Clinton mandated that any rafters captured be detained at Guantanamo Bay Naval Base. About 31,000 of those 33,000 were detained at the base while many others were lost at sea. Even though this process of immigration is risky and dangerous, many are worried that the balseros crisis will happen again.

The extension of Title 42

On December 27th, 2022, the U.S. Supreme Court voted to keep Title 42 in place, allowing asylum-seekers to be turned away at the border, even though it would have expired at the end of 2022. It is now in place indefinitely after 19 Republican state attorneys general filed an emergency appeal to the Supreme Court to keep it in place. U.S. District Judge Emmet Sullivan ruled that Title 42 should expire at the end of this year because the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s implementation of this policy was “arbitrary and capricious.” While many, such as Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch, argued that the public-health justification of Title 42’s implementation has lapsed, they still voted for it to stay in place. Some Democrats, such as California Governor Gavin Newsom, think that if Title 42 is ended, the asylum system would break. White House Press Secretary Karine Jean-Pierre said in a statement that “Title 42 is a public health measure, not an immigration enforcement measure, and it should not be extended indefinitely.” Yet, the Biden Administration is complying with the Supreme Court’s Order and enforcing Title 42, offering no alternative to those trying to seek asylum on the border.

However, there are steps in the right direction being made. In January of 2023, Biden issued an executive order restricting asylum applications on the U.S.-Mexico border for four countries, Cuba, Venezuela, Nicaragua, and Haiti. As mentioned in the first paragraph, the qualifications for asylum applications are steep, including needing a sponsor in the U.S. that can sponsor you financially. If one goes to the border without a sponsor, they will be turned away and the “Remain in Mexico” policy under Title 42 will be in effect. This Executive Order talks about expanding legal pathways for safe, orderly, humane, and legal migration. This includes increasing humanitarian assistance to Mexico and Central America, expanding the parole process, launching an online appointment portal to reduce overcrowding and wait times at the border, and tripling refugee resettlement from the Western Hemisphere. Biden has also reopened the U.S. embassy in Havana for visa applications allowing some an official route to emigration to the U.S.

Conclusion

After the extension of Title 42 by the Supreme Court, the NGO, The Washington Office on Latin America, WOLA, gave a list of 5 reasons why Title 42 must end immediately. Title 42 was not designed to protect public health, it creates a discriminatory system because it targets four specific countries, it puts people in need of protection in danger, and it undermines the U.S. ability to promote a protection-centered response to regional migration. However, the foremost reason is that Title 42 is illegal. It denies refugees protection from life-or-death situations. The Biden administration expels around 2,500 migrants every day. Section 1158 of Title 8 of the U.S. Code does not allow for the blocking of fundamental protection and safety of migrants seeking asylum. Instead of perpetuating and prolonging a broken immigration system, it would be beneficial to invest time and resources in other areas. This would start with restoring the right of all refugees to seek asylum at the border. Using a COVID-era policy is not a justification anymore to keep implementing this law. Another is ensuring humanitarian support for the migrants that are arriving while also coordinating the response of federal, state, and local organizations to make sure everyone gets the same resources and treatment. Finally, there needs to be improvements to the adjudication capacity and resources, as the wait time could be anywhere from 2 months to 1 year. There is a shortage of lawyers at the border who have impossible caseloads. By increasing the number of public defenders at the border, due process can still be ensured in a timely manner. The US immigration system has been broken for decades. Every day we wait to fix or come up with a new policy, thousands of people fall through the cracks and succumb to the danger they are running from. The system needs to be fixed, for the sake of rebuilding our asylum process and the democratic values that the U.S. was founded on.

Amnesty for the Innocent: Relocating Russian Dissenters Following Putin’s War in Ukraine

Staff Writer Jacob Paquette outlines a European resettlement strategy for Russian migrants fleeing Putin’s Russia, focusing on strategic resettlement, successful social & economic integration, and the benefits of such an approach for Russian-speaking communities in the Baltic states.

The current migrant crisis in Europe completely outpaces any similar crisis on the continent since World War II. A month into the offensive Russian war in Ukraine, nearly 4 million Ukrainians had fled the country seeking asylum abroad, with an additional 7 million being internally displaced. With the war continuing to escalate, more refugees are sure to continue pouring from the country.

Though those refugees fleeing Ukraine seem to get the majority of the press attention, as well as the majority of the assistance from Western nations (and all for good reason), the crisis has also sparked a similar exodus of Russians and Belarusians from their respective countries. A mid-March survey concluded that roughly 300,000 Russians have left Russia since the start of the invasion of Ukraine, while liberal estimates predict the real number could exceed one million persons having already left, all largely due to crippling Western sanctions, the total collapse of the Russian ruble and the Russian economy, and a wide-scale authoritarian crackdown by the Russian federal government. At the start of the Russian invasion, thousands of Russians took to the streets, in over 70 cities, to protest the war; on the first day of the war the total number of protestors arrested was 1,900 while over 13,000 protestors had been arrested a month into the war, amounting to the largest scale protests and political arrests in the country’s modern history. Soon after, Russia would take draconian measures to ban social media outlets such as Facebook and Twitter, crack down on various independent media outlets (falsely labeling them as “foreign agents”), and implement a new law allowing the government to sentence individuals to up to 15 years of imprisonment for defying the Kremlin’s narrative regarding the war. Meanwhile, the Russian economy was totally ruined as Western sanctions and popular pressure caused foreign capital and investment to flee overnight, unemployment to soar, the ruble to deflate, and the purchasing power of ordinary Russians to dwindle. As the future economic prospects for all Russians suddenly changed for the worse, those Russians with the means to leave have done so. And because conditions within Russia seem to only be getting worse, more are sure to follow those who have already left.

Most of those Russian nationals leaving Russia consist of the urban college educated youth as well as the middle class. The young and the middle class were most likely to work in the service sector and with foreign companies before sanctions, while this section of the population is also most likely to be critical of Kremlin talking points regarding the war. Additionally, middle class Russians (aside from perhaps Russia’s elite, affluent ruling class) have the most financial means to resettle, while they also have comparatively better career opportunities abroad; young Russians also tend to have better skill sets for work abroad and have fewer commitments and responsibilities tying them to Russia—such as family or an existing committed career—and many seek to avoid being drafted into the Russian armed forces in the midst of war. Generally, the majority of those who are leaving Russia are “academics, IT specialists, journalists, bloggers” or protestors, who all fear that the unpredictable climate within Russia could quickly make their lives impossible. Most of these Russians fleeing are destined for countries which offer visa-free entry for Russian citizens, namely Georgia, and Armenia, with other common destinations including Azerbaijan, Turkey, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, and Serbia to name a few. Though the Russians fleeing predominantly consist of individuals who are adversarial towards, or are at least skeptical of, Putin’s regime, their reception has been somewhat mixed. In Georgia, for example, Russian nationals in the country have been experiencing high degrees of discrimination, both on the street in day-to-day life and while looking for apartments and opening Georgian bank accounts. That being said, the majority of Georgians remain receptive to Russian expatriates and for good reason, as Russians leaving Russia offer the country a valuable, new, educated labor market. With more than 1,000 companies being founded by Russian nationals within Georgia in the last month, the benefits of taking on Russian expatriates are undeniable. But, despite their somewhat mixed reception in Georgia and other countries, Russians have been received far worse in Western countries, namely in the European Union and in North America. The Czech Republic, Latvia, and Lithuania have all announced that they will no longer be processing visa applications from Russian applicants due to the war in Ukraine, while Greece has placed additional restrictions on Russian nationals seeking visas; meanwhile, instances of hate crimes and discrimination against individual Russians abroad in Europe and North America have skyrocketed following the invasion. Therefore, much of the world suddenly seems to be a very hostile place to many Russians, and as Russians continue to flee and seek out safe havens from political persecution and economic ruin, those countries which accommodate the masses of young and educated Russians leaving will have much to gain. Countries across Europe, but namely those Baltic states with large Russian-speaking communities, should embrace the current wave of migrants from Russia, both as a means of securing talent and educated labor but also as a contribution to the Western strategy of punishing Russia for its ongoing offensive invasion.

Putting entry and visa requirements aside, countries in Central and Eastern Europe are among the most suited to take in Russian expatriates. For one, the Baltic countries of Estonia and Latvia are particularly suitable for Russian immigrants, as both countries already house large Russian diaspora communities. Estonia’s population consists roughly of 24% native Russian speakers, with the concentration of these ethnic Russians mainly being in the country’s Northeast, around the urban center of Narva where the percentage of Russian speakers accounts for 90% of the city’s population. Latvia maintains a similarly sized Russian population, consisting of 25% of the country’s total population, over 35% of the population of Latvia’s capital city, Riga, and 56% of the population of the country’s second-largest city, Daugavpils. Therefore, with a large Russian speaking community already being present, urban centers like Tallinn, Riga, Daugavpils, and Narva all make realistic and comfortable options for Russians looking for new homes abroad.

Additionally, repatriating Russian nationals could serve as a highly effective strategy to encourage economic growth in some of the poorest parts of the Baltic States. For example, Latvia’s poorest region, Latgale, also contains a large Russian speaking majority, making up 60% of the region’s population. Should educated, young and middle class Russians seek residency in Latvia, they will likely resettle either in Riga or in parts of Latgale, such as the large post-industrial city of Daugavpils, as these are the two main areas with dominant or large Russian-speaking communities. Once in the country, these expatriates might contribute greatly to the economic rebirth of the country; cities like Narva and Daugavpils are both post-industrial cities where poverty and poor quality education have proven to be massive problems. Should Russian entrepreneurs resettle in Daugavpils or Narva, and start new businesses, they will surely bring with them great employment opportunities for members of those respective communities already living there, possibly leading to the revitalization of these urban areas.. And should Russian expatriates also settle in Riga or Tallinn, they can further contribute to the relative success that these two cities have been experiencing in recent years, in terms of economic development.

Furthermore, Estonia specifically is an exceptional possible destination for many Russian expatriates, specifically those who work in fields relating to IT (a large portion of those Russians fleeing, as already discussed). Information and Communications Technology has quickly become Estonia’s dominant economic sector, contributing the most to the country’s GDP growth over the past decade. With over 6,000 IT companies calling the small Baltic country of 1.3 million home, and with Russian language, similarly to the Latvian case, still playing a major role in daily urban and business life, Estonia makes for an unrefusable opportunity for many Russians looking for better job security abroad.

Aside from contributing to economic success, Russian immigrants might also deradicalize the Russian-speaking communities already in the Baltic. In Estonia, 89% of ethnic-Russians watch Russian state media, while only 49% follow Western media outlets; in Latvia a stark 97% of Russian-speakers watch state media while only 10% follow Western media outlets. Looking at these figures, it becomes quite clear that there is more than just a linguistic divide between Baltic-Russians and dominant Baltic national identities like Latvians or Estonians; there is also a deep political divide partially originating from the forms of media that individuals choose to consume. By contrast, the largely urban educated and young population of Russians leaving Russia are far less likely to buy into Kremlin narratives; therefore, if the Baltic countries were to take in some of these more liberal and democratically minded Russians, this could easily contribute to diluting the influence of the Kremlin within Baltic-Russian communities and alleviate their radicalism over time.

But before any of the potential positive effects of Russian expatriates resettling in the Baltic can be felt, Estonia and Latvia will need to adjust their visa policies towards Russians. As previously mentioned, Latvia has suspended the processing of all visa applications for applicants from Russia, a move which clearly must be reversed. Estonia and Latvia should offer Russians six months to a year of visa-free stay in their respective countries, and they should offer a clear pathway thereafter towards permanent residency and citizenship. Of course, it is not enough to merely accept these migrants. The respective Baltic states, and any country accepting migrants for that matter, must do all they can to integrate these migrants into their broader, national identities and into national society. Baltic countries could offer short-term business loans to Russian migrants who meet certain qualifications and who agree to remain in the country for a certain period of time to increase their economic integration with the host society, and Latvia and Estonia could offer subsidized formal instruction in their respective national languages to improve rates of social integration. Such actions would also need to be accompanied with a massive reworking of the media narrative surrounding Russians and Russian-speakers in the Baltic. Instead of allowing media outlets to malign Russian nationals as being totally loyal to the Kremlin and complicit in the actions of the Putin regime, government spokespersons should actively counter these narratives; instead, they should paint a more fair picture of ethnic Russians, as a people living subjugated by an authoritarian regime, who live in fear for their lives and their families, and who need the help of the West in order to achieve fair standards of living. Without such a shifting of the mainstream narrative within the regional context of the Baltic, Russophobia is certain to continue to increase, social integration will be made more difficult for those Russian-speakers already living within the Baltic, and the possible slew of benefits from accepting Russian migrants will be discarded, with those benefits instead being directed to countries accepting those Russians fleeing Putin’s regime.

Even worse, if these migrants are not given good opportunities wherever they may resettle, many of them are sure to return to Russia, where they will continue to live and work under the Kremlin’s iron fist, contributing to economic productivity and the growth of the Russian economy. For a West concerned with punishing Russia after its offensive invasion of Ukraine, accepting Russian migrants plays directly against Putin’s hand. It gives some of Russia’s brightest and most productive the promise of a free, safe, and prosperous future out of the reach of authoritarian strongmen, and it eliminates nearly any incentive to ever return to Russia, permanently depriving Russia of its next generation of skilled labor.

Putting all else aside, the very moral legitimacy of Western liberal democracy depends on our reaction to authoritarian leaders, like Putin, who threaten peace and antagonize innocent civilians at home and abroad. The West has responded positively by helping Ukrainian victims of the Russian invasion restart their lives, safe from the shelling of Kharkiv or the bombardments of Mariupol. Meanwhile the West has ignored the desperate cries of so many Russians, who too live in fear for their lives, their freedom, and their livelihoods. Only by answering the calls of all those in need can the West truly fulfill its prerogative in safeguarding human rights and human dignity the world over.

How Local Governments Help Afghan Refugees

Staff Writer Hannah Kandall evaluates the contributions of state and municipal governments in the process of refugee resettlement, pertaining to the recent arrival of thousands of Afghan refugees in America.

Anti-immigration sentiment rings loudly throughout the American political scene. However, with a recent influx of refugees from Afghanistan, the United States has to pool together depleted resources in order to help those escaping the Taliban. Citizens of Afghanistan continue to face human rights abuses at the hands of the Taliban, exemplified by a deadly attack on a school in Kabul. Not only are civilians facing this terror, but so are thousands of Afghan citizens who assisted the United States military during the two decades of military occupation.

Immigration is a multilateral issue and pools resources from every level of the government, including local government. Municipal governments play an intricate role in integrating refugees with the communities they arrive in, and their role is often overlooked and under-funded.

What is Happening in Afghanistan?

After 20 years of United States military presence in Afghanistan, the United States pulled almost 60,000 troops out of the country in the summer of 2021. The aftermath left the nation of Afghanistan in shambles and vulnerable to the Taliban. The terrorist organization rapidly gained power, causing thousands to flee the nation. Over 122,000 people have evacuated Afghanistan including Afghan citizens, Afghan interpreters, and United States citizens. Those fleeing Afghanistan qualify for a Special Immigrant Visa (SIV) under U.S. law; however, the process of obtaining a SIV takes 14 steps over the span of months—keeping 65,000 applicants stuck in Afghanistan. The Biden administration is working to expand access to visas through means of work or humanitarian parole to allow more refugees into the United States in as swift a fashion as possible.

Refugee Resettlement in America

Whether an SIV is required, or a refugee is on humanitarian parole, those who come to America are sent to one of seven military bases for health screenings and work authorization. This process can take longer than one week, and as of October 3, 2021, there are 53,000 refugees waiting across the seven military bases. When the initial screenings are completed, refugees are placed with resettlement organizations, which help them obtain housing, utilities, furniture, food, work, and English literacy training. Marisol Girela, the Associate Vice President of social programs at RAICES in San Antonio, Texas, stated that their organization alone has seen a dramatic increase in refugees arriving over the summer. Many resettlement organizations, such as RAICES, work closely with local governments, but federal barriers block effective partnerships.

Federal Barriers to Effective Resettlement

The Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society (HIAS) sued the Trump administration in November of 2020 over an executive order passed by President Trump. The goal of the executive order was to require municipal governments to obtain approval for refugee resettlement programs on the city, state, and federal level. This order put up more bureaucratic barriers when it comes to refugee resettlement, and HIAS, along with Church World Services and the Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Services, sued the administration on the basis of the undue burden that the executive order placed on resettlement agencies who are legally required to obtain formal city and state approval for their work.

The Trump administration’s anti-immigrant ideology strained refugee resettlement organizations, who do crucial work on the local level. Reuters acknowledged that the decrease in immigration caused resettlement groups to downsize, as they operate as nonprofits. With the current increase in refugees from Afghanistan, these groups are too under-funded and under-staffed to provide the best quality assistance to the refugees. They are left scrambling for resources, due to the quick and urgent demand for safety in America. As of September 2021, President Biden’s administration requested funding from Congress to resettle 65,000 Afghan refugees this fall and eventually 95,000 refugees by September 2022. The administration told state governors and refugee resettlement coordinators to prepare themselves for a sharp increase in demand, as refugees are coming to America whether Congress grants the administration funding or not.

Local Government’s Role in Resettling Afghan Refugees

The bulk of refugee resettlement is done at the local level with resettlement organizations. Cities across America such as Rochester, NY, Buffalo, NY, Cleveland, OH, Pittsburgh, PA, and Elizabeth, NJ have committed to welcoming refugees and actively push back against anti-immigrant rhetoric. Support for resettlement comes from all levels, from the U.N. to private citizens’ donations, but it is a city or town’s local government that gets into the intricacies of resettlement. Yet, due to aforementioned federal barriers, local authorities are isolated from policymaking on the topic of resettlement, but still placed with the majority of the responsibilities. Additionally, issues that face local governments in the wake of COVID-19 impact refugees particularly hard. Cities are currently struggling with a housing boom which makes finding a larger, family home increasingly difficult. These are the kinds of homes refugee families are in need of. Furthermore, there is a shortage of rental properties in cities across America, and landlords are hesitant to rent to those without credit as they are already losing out due to the economic impacts of COVID-19. Difficulties that municipal governments face are exacerbated when those strained resources are needed to help incoming refugees.

According to the German Marshall Fund of the United States, local governments play an essential role in coordinating medical appointments, English literacy courses, and job training. Community leaders know what resources are needed to effectively resettle in their unique location in terms of cost of living and neighborhood engagement. The federal government’s Afghan Placement and Assistance Program, while effectively expanding refugee assistance, does not take diverse housing costs across America into account which can lead to further fiscal difficulties. By processing a deep understanding of the municipality, local officials and organizations are equipped to know the intricacies of resettlement in their particular community. Additionally, people in a community tend to trust their local leaders, so when their mayor, town supervisor, or city council shows active support for refugees, it puts pressure on federal legislators to do the same by continuing to expand access to America.

Refugee Resettlement in the District of Columbia

Due to the sudden nature of increased violence in Afghanistan, those who flee are coming to America with incomplete documentation, a single bag of possessions, and barely any support system. Dire needs for necessities such as clothing, housing, and food prove the local government’s vital role in directly assisting refugees. The nation’s capital can serve as an example for how local governments aid in refugee resettlement, especially for those coming to America with little to no resources. The D.C. Office of Refugee Resettlement (DCORR) provides “temporary assistance for needy families, medical assistance and screenings, employment services, case management services, English language training, education assistance, and foster care placement.” Children accompanied by parents and unaccompanied children are eligible for the Children’s Health Insurance Program and Refugee Cash Assistance. Aside from gaining access to medical assistance and screenings, refugees settling in the District of Columbia also are eligible to receive health literacy in physical and emotional wellness services through the D.C. Department of Human Services. Refugees that come to the District of Columbia are commonly moved to the city from the military base for refugees in Fort Lee, Virginia and then, through the DCORR, placed with Catholic Charities Refugee Services or Lutheran Immigrant and Refugee Services—who are a part of the aforementioned lawsuit with HIAS. Nonprofits serve as the liaison between both federal and local governments and the refugees themselves, ensuring that the services offered by the city governments make it to the refugees. This can include coordinating housing arrangements, picking up families and individuals from military bases, and assistance with benefit applications for social security and Medicaid. Both Catholic Charities Refugee Services and Lutheran Immigrant and Refugee Services in the District of Columbia provide these services to the refugee community. Their role is important to ensure direct connections are made with the refugees who arrive from Afghanistan.

The Community’s Role

Local governments and nonprofits play a critical role in refugee resettlement, but so do members of the community. In the District of Columbia, local businesses and charities are accepting donations. Items that are in demand include household items, utensils and cookware, furniture, clothes, food, and toiletries. Along with accepting donations, the same organizations are putting out Amazon wish lists for those resettling in America from Afghanistan. Organizations are also coordinating volunteers to help set up refugees with apartments, and rides from the airport. Support for Afghan refugees starts from the top and trickles down to individual volunteers and donors. HIAS has set up resources and instructions to contact federal representatives to advocate for greater support for refugees.

The increase in refugees coming to America is sudden, but urgent. Those coming from Afghanistan are vulnerable to the Taliban and are relying on American organizations to provide safety and stability. Local governments are not often thought of in this process, but they are immensely important to it. However, years of depleting resources from refugee resettlement at the federal level has trickled down to hit local governments, as they carry the bulk of resettlement responsibilities for vulnerable populations with the least number of resources.

The Immigration Battle: How the U.S. and Germany’s Respective Immigration Models Affect Immigrant Economic Participation

Executive Editor Diana Roy compares the United States and Germany’s immigration models and analyzes how they affect immigrant participation in the economic sector.

The 2015 migrant crisis was one of the worst in global history. As a result of the ongoing conflicts in Syria, Afghanistan, and Iraq, as well as the unbearable living conditions in Eritrea, Kosovo, Yemen, and other nearby states, over 19.5 million refugees fled their native countries, mostly in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, and arrived at Europe’s and Asia’s borders in unprecedented numbers. This sudden influx of people by both land and sea into the European Union (EU), Germany in particular, created deep divisions within society over how to best cope with the vast amount of incoming refugees, many of whom could not speak the local language and had no documented proof of their existence. In addition to Europe, the United States was another preferred destination for refugees, although reaching America’s borders was a greater logistical challenge.

Nonetheless, with the highest immigration rate out of all 28 EU countries and another whose existence is essentially built on the backs of immigrants, Germany and the United States are two of the most salient states to examine when analyzing the impacts of the recent immigration crisis. Both of these respective nations pride themselves on their ability to serve as a beacon of hope, change, and freedom for all, and while they share a lot of the same immigration laws and issues, they also differ immensely in their long-term treatment and adjustment plans for immigrants. This disparity, despite their similar roles as two of the most popular migration destinations in the world, downplays the important role and potential impact that immigrants can have on the country that they move to, especially in the economic sector. Despite the popular claim that immigrants steal native jobs, the economic and employment sector is often analyzed to determine how prosperous a state is. As a result, understanding how immigrants are accepted into the employment division in Germany and the United States is crucial to understanding the complexities of the Western immigration debate.

Overview of American and German Immigration History

The United States

Often said to be a “nation of immigrants,” the United States has been a desirable destination for refugees and immigrants alike for hundreds of years due to its promises of change and the opportunity to achieve the coveted ‘American Dream.’ However, immigration to the United States really began to take flight when an 1850 census included questions regarding nativity for the first time. Data from that census revealed that there were 2.2 million immigrants residing in the United States at that time, making up about 10 percent of the overall population. In the next 60 years, those numbers increased as people began to leave Europe because of lack of employment, crop failure, rising taxes, and famine, with the majority coming from England, Ireland, and Germany. In that period of time, the percentage of foreign-born individuals in the United States stayed between 13 and 15 percent, eventually reaching a peak of 14.8 percent in 1890.

However, the culmination of the Great Depression, World War II, and new restrictive immigration laws that only let in strictly northern and western Europeans significantly decreased the rate at which people were coming into the U.S., leading to a low of 9.6 million immigrants, or 4.7 percent of the total U.S. population in 1970. After 1970, the number of immigrants residing in the United States quickly increased as more and more people immigrated from Latin America and Asia primarily. New laws including the Immigration Act of 1965 that abolished admission quotas, paired with the nation’s growing economy, led to an all-time high of more than 44.4 million immigrants in the United States as of 2017.

Yet the United States is no stranger to restrictive immigration laws; in 1882, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act suspending the immigration of Chinese workers for ten years, and in 1892, it passed the Act to Prohibit the Coming of Chinese Persons into the United States. Yet, despite those restrictions, which were later repealed, and the continuation of those social attitudes by many Americans today, the United States also made significant strides in welcoming immigrants and refugees alike in later years. The most notable ones were the Refugee Relief Act of 1953 which “authorized the admission of up to 205,000 non-quota immigrants fleeing Europe,” and the Refugee Act of 1980, which established a new system for “processing and admitting refugees from overseas” and formally defined a “refugee” as “any person… who is unable or unwilling to return to [a] country because of persecution or a well-founded fear of persecution.”

Nonetheless, since the September 2001 attacks by al-Qaeda, there has been an increased focus on immigration, specifically on immigrants from the MENA region, as well as calls for a return to more restrictive immigration laws. During his 2016 presidential campaign and throughout his presidency, President Donald Trump continuously pushed for a crackdown on illegal immigration by enacting the ‘Muslim ban,’ which has been shot down in many states for being unconstitutional, and building a wall at the southern border. President Trump's anti-immigrant rhetoric is primarily targeted towards Mexicans and Muslims, although he recently called for increased visa restrictions on Chinese citizens as well. This rhetoric, although in opposition to the country’s global role as a beacon of hope and freedom, is strikingly similar to the country’s anti-immigrant behavior from over a hundred years ago.

Germany

Whereas the United States faced an unprecedented influx of immigrants in the 19th and 20th centuries, Germany battled the opposite; between 1820 and 1920, as a result of war, famine, and political upheaval, around 6 million Germans left their home country in search of opportunity. However, around 1890 the emigration rate slowed down considerably as the German Empire entered a period of industrialization, attracting both those who had left as well as foreign workers who saw the potential to make a big profit in the newfound coal and steel industries.

Yet while Germany was a country made up of immigrants, it was not a country whose society was very welcoming towards those who were foreign-born. In fact, xenophobic attitudes manifested themselves drastically in the 1920s under Adolf Hitler and the Nazi party who advocated for the creation of a “pure” and “superior” German race, who he referred to as the “Aryan race.” This translated into nationalistic and anti-Semitic world views and a strong hatred for those who were neither German nor white. This anti-immigrant behavior later manifested itself into a 1973 government act known as the “Recruitment Ban”; this ban essentially ended the “era of foreign labor recruitment” of “guest workers” to West Germany and prevented them from entering the country from states who were not part of the European Economic Community at the time. Post-1973, immigration rates in Germany actually increased when the Soviet Union fell and the situation in Yugoslavia turned bloody and violent. Yet with the new influx of immigrants, xenophobic behavior also grew and mob violence broke out across many Germany cities and towns. Another significant anti-immigrant act was also passed in 2005 and became known as The Immigration Act or the Residence Act; this act essentially established Germany as a “country of immigration” with a legal duty towards integration. Having experienced the extremist views under Hitler, this fundamentally changed the way in which Germany presented itself in the international community as an immigrant ally.

Since joining as a member of the EU in 1957, Germany has become the second most popular migration destination in the EU after the United Kingdom, with approximately 15.96 million immigrants living in the country by 2011, amounting to about 19 percent of the population. Yet with the 2015 migrant crisis and the influx of migrants from the Middle East in particular, the population in Germany rose to 82.2 million people, an increase of 978,000 or 1.2 percent. In that same year, immigration to Germany totaled 2.14 million people, a 46 percent increase from 2014. As a response to the immense wave of immigrants fleeing the Middle East, Africa, and Asia, German Chancellor Angela Merkel called for an open border migration policy that would allow Germany to welcome those from primarily Afghanistan, Syria, and Iraq. While Merkel was alone in this decision and her popularity levels dropped significantly, immigration to Germany in recent years has slowed considerably, with most individuals originating from Turkey and Poland.

The United States: Geared Towards Permanent Residency

At present, the current discourse among scholars in the field of immigration is that the American immigration system is more exclusionary and geared toward permanent residency. For those immigrating to the United States, the process to become a U.S. citizen can be done one of four different ways: acquiring citizenship by birth, acquisition, derivation, or naturalization. Immigrants also have the option of obtaining a Green Card or a Permanent Resident Card, which would allow them to permanently live and work in the United States. While the process to become a U.S. citizen is a long and difficult one, it is a process and a system that is designed to grant someone permanent residency and not simply a temporary stay. While the United States does offer temporary work, school, and travel visas, those have a time limit, and after a certain amount of time, the individual must return to their home country unless they choose to overstay their visa and risk deportation. Obtaining permanent residency is the only way to live in the United States in the long-run without facing potential repercussions with immigration authorities.

Furthermore, the United States’s immigration system has an exclusionary design which is made more difficult due to the length of time that it takes to become a U.S. citizen, as well as the necessary documented proof and other government obstacles that must be overcome. The citizenship process tends to be a long and arduous one if citizenship by birth is not an option, and much like the vetting process for refugees, it can take up to 18-24 months including an array of comprehensive interviews and security checks that are completed by the Department of Homeland Security and the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services. The entirety of this process first includes getting sponsored by a U.S. citizen, be it a relative or an employer. To even be considered for an immigrant visa, the immigrant must be sponsored, which then leads to the submission of a petition for citizenship. After the petition is filed, the immigrant must pay processing fees, submit financial and supporting documents, and go through an interview; if the immigrant passes the interview, he or she will then be granted their immigrant visa and legally be allowed to enter the United States. This process is exclusionary in nature because many immigrants either do not have the necessary documentation and proof of their existence, do not have the financial means to pay the processing fees, and/or do not have someone residing in the U.S. that will sponsor their visa. As a result, only a fraction of immigrants applying for visas are accepted.

Additionally, despite immigration being one of the most salient issues a country can face, misperceptions still persist, especially regarding how immigration affects a country’s economy and workforce. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), the U.S. labor force, defined by the BLS as “all people age 16 and older who are classified as either employed and unemployed,” was approximately 160 million people in January 2018. There is also the Labor Force Participation Rate (LFPR), which is the percentage of people in the labor force who are either working or actively looking for work. Out of that 160 million in the labor force, immigrant laborers, mostly from Latin America, make up a record high of 17 percent as of 2019, amounting to roughly 27,200,000 people. With 2019, the economy is said to be on track to have the same success as it did in 2018, where output increased by $560 billion and grew by 3.1 percent.

Yet irregardless of the aforementioned data, many immigration critics argue that immigrants, regardless of their legal status or the percentage that they hold in the labor force, “steal American jobs” and “hurt the American economy.” President Trump is one such proponent of this belief; in November 2018, he stated that “Illegal immigration hurts American workers, burdens American taxpayers, and undermines public safety” in addition to them “taking precious resources away from the poorest Americans who need them most.'' However, while many stand behind that belief, the data reveals that the U.S. economy relies heavily on immigrant laborers and foreign-born workers in the labor force to contribute to national economic growth. A 2017 report by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine found that “immigration has an overall positive impact on long-run economic growth in the U.S.” Furthermore, the report revealed that second generation immigrants are “among the strongest fiscal and economic contributors” in the country, as they contribute around $1,700 annually per person. That data, paired with the fact that there has been a recent increase in more educated immigrants, demonstrates how immigrants are and will continue to be economically beneficial.